By Jae Jones

African-Americans have long embraced the tradition of honoring Thanksgiving. Even during slavery time, Africans took time to be thankful for what they had, which of course was not much. In 1777, when the Continental Congress delivered a decree for the 13 colonies to give thanks for reaching a victory over the British at Saratoga, the Africans also took part in the celebration throughout the region. And, the tradition continued as a custom of rejoicing for rain to break droughts and plenty of harvest.

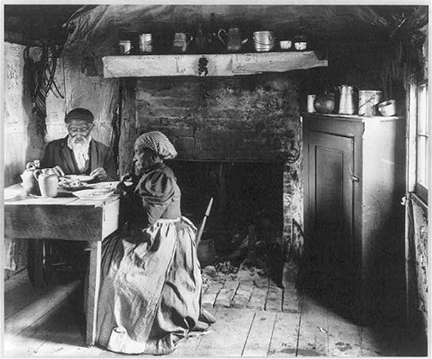

So, what did the slaves eat on this day they were allowed to celebrate? The slaves who worked in the fields would often go out and catch wild game for their family and close slave friends. The women would prepare cornmeal cakes, or pone cakes to go along with the game. The house slaves had it better than the field slaves; house slaves feasted on the leftovers from the “main house” after the slave-owners finished their meals.

A forgotten fact, Thanksgiving started off as a church oriented celebration for the Black community. African American pastors often gave sermons that could be heard loud and clear through the small black churches. The sermons would be about struggles, hopes, fears, and triumphs. The sermons usually grieved the institution of slavery; the suffering of the black people; and often pleaded for that an awakening of a slave-free America would some day come soon.

African Methodist Episcopalian cleric, Reverend Benjamin Arnett stirred a predominantly black congregation on November 30, 1876 with Biblically inspired words:

…we call on all American citizens to love their country, and look not on the sins of the past, but arming ourselves for the conflict of the future, girding ourselves in the habiliments of Righteousness, march forth with the courage of a Numidian lion and with the confidence of a Roman Gladiator, and meet the demands of the age, and satisfy the duties of the hour…”

Then let the grand Centennial Thanksgiving song be heard and sung in every house of God; and in every home may thanksgiving sounds be heard, for our race has been emancipated, enfranchised and are now educating, and have the gospel preached to them.

In 1863, Lincoln signed the proclamation of a national Thanksgiving Day, unifying the various regional practices that had already been taking place throughout the nation.

I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are so journing in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.”

Some slaves saw the holidays as an opportunity to escape. They took advantage of relaxed work schedules and the holiday travels of slaveholders, who were too far away to stop them. While some slaveholders treated the holiday as any other workday, there have been numerous recordings of a variety of holiday traditions, including the suspension of work for celebration and family visits. Because many slaves had spouses, children, and family who were owned by different masters, and who lived on other properties. Slaves often requested passes to travel and visit family during this time. Some slaves used the passes to explain their presence on the road and delay the discovery of their escape, though their masters’ expectation was they would soon return from their “family visit.”

Today, many African-Americans still spend time traveling and visiting family and friends during the holiday. But, many have moved away from spending Thanksgiving Day in church; that practice has long been forgotten by many. Thanksgiving today is not recognized for the same reasons as it was years ago. Today it is a day that spent with family and friends being thankful for one’s many blessings.