By John Broadway

As Americans engage with Black history this month, we want to take time to honor and understand how the economic exploitation of Black Americans has shaped much of this nation’s history. In this blog post, we’re taking a look at the many forms this economic exploitation has taken throughout American history and what they teach about the issues we face today.

Original Sin

Let’s go back to the 17th century when American colonies began codifying racialized “slave codes,” laws that stated, among other things, that anyone whose mother is a slave shall be relegated to slavery for life. Then, to quell a growing abolitionist movement, proponents of slavery proliferated the ideology of white supremacy – backed by racist pseudo-scientific theories like phrenology, for one. Proponents of slavery wielded White supremacy to justify the, according to one recent estimate, approximately 5.9 to 14 trillion dollars worth of unpaid labor stolen from enslaved Africans.

White supremacy helped mold a racial hierarchy that remains entrenched today and continued the economic exploitation in new forms following the abolition of slavery.

The “Reconstruction” of Stolen Labor

The Reconstruction Era was supposed to remedy the sins of slavery. But Emancipation decimated the South’s economy. As a result, throughout this era, the South “reconstructed” its methods for stealing labor and wages from Black Americans as a means to prop up the economy.

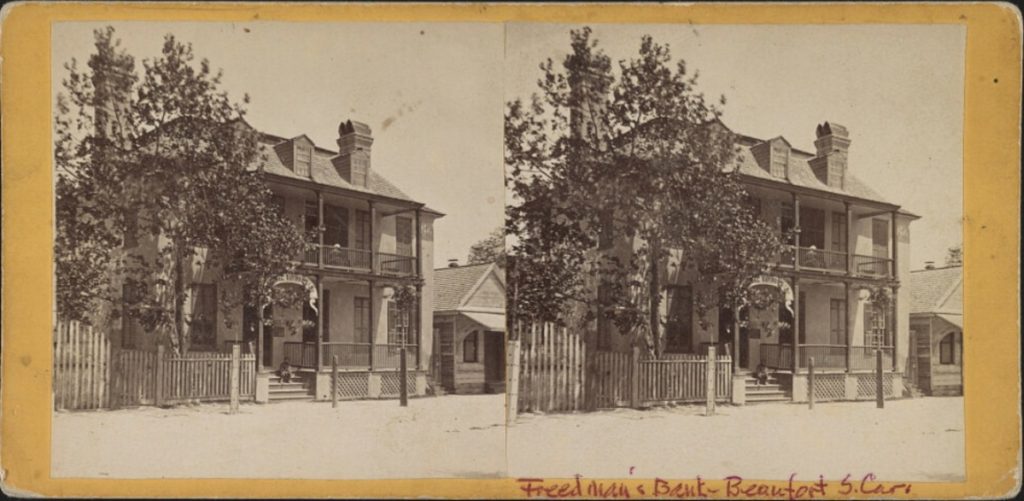

During Reconstruction, the South instituted Black codes, which, among other things, criminalized the free movement of African-Americans. These codes were so intentionally oppressive that some statutes were lifted directly from the slave codes, merely replacing the word “slave” with “freedman.” The convict leasing system — another thinly veiled extension of slavery — capitalized on Blacks’ targeted criminalization by leasing convicts to plantation owners for unpaid labor.

Wage Theft

Immediately after the Civil War, many former slaves established subsistence farms on land abandoned by fleeing white Southerners. President Andrew Johnson, a Southerner and former slaveholder, restored this land to its white owners, which reduced many freedmen to economic dependency.

Seeking autonomy and independence, the freedmen refused to sign contracts that required gang labor, and sharecropping emerged as a compromise. Landowners divided plantations into 20- to 50-acre plots suitable for farming by a single-family. In exchange for the use of land, a cabin, and supplies, sharecroppers agreed to raise a cash crop and give a portion (typically half) of the harvest to the landowner. Landowners extended credit to sharecroppers to buy goods and charged high-interest rates, sometimes as high as 70 percent a year, creating a system of economic dependence and poverty.

The debt to the landowners compounded year after year until there was no way to ever repay it, which tied sharecroppers to plantation lands without an option to leave. This vicious cycle essentially turned sharecropping into another form of servitude, and generations of families were impoverished under Jim Crow Laws, restricting mobility, forcing many African-Americans to remain under the thumb of these exploitative practices.