By Diane Xavier

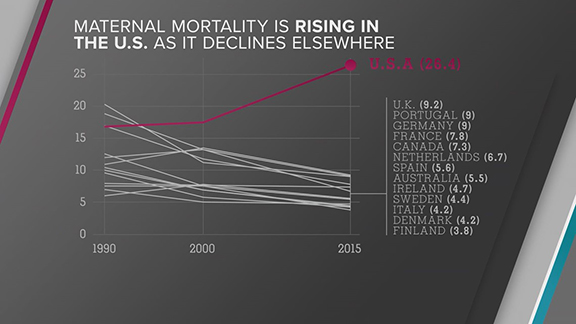

Black women are twice as likely as White women to die due to complications of pregnancy or childbirth. Texas has the eighth-highest maternal mortality rate in the United States, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Moreover, African American women lag behind other races when it comes to getting the health care they need in general.

Advocating for the overall wellbeing of Black women and girls, Friendship-West Baptist Church’s Center for Gender Justice hosted a virtual lecture series March 30. It was held during Women’s History month to address these issues and empower Black women to speak up and take action on protecting their mental and physical health.

“March gives us an opportunity to be intentional about recognizing women’s contributions to the global society, and to deal with the challenges and inequities faced by women to organize efforts to dismantle social structures that inflict physical and structural violence against women and girls,” said Rev. Danielle Ayers, pastor of justice at Friendship-West Baptist Church. The BWCGJ is dedicated to addressing the needs of women and girls year-round. The church is a place where justice, peace, love, liberation and healing can be lived out.”

The event, called The Holy Hush: The Physical and Mental Well Being of Black Women, was part of the Broughton-Wells Lecture Series. It featured Ayers, who moderated the event; Rev. Dr. Irie Lynn Session, co-pastor of The Gathering, A Womanist Church; Marsha Jones, executive director of The Afiya Center; and Dr. Stacie McCormick and D’Andra Willis of The Afiya Center.

Lauren Franklin, a member of BWCGJ, welcomed attendees and provided a quick overview of the program.

“This year’s focus on the Broughton-Wells lecture series is the gift of the Black woman, promoting hope and providing healing,” Franklin said. “This lecture series focuses on the stories of Black girls by creating a dynamic learning community focused on education mobilization on organization through the church and community and training us to become advocates for issues related to the wellbeing of Black women and girls while unpacking womanist theology. The censoring of the voices and stories of Black women and girls is critical. And tonight’s topic will be just that. We do know that this topic may be triggering for some as it does deal with reproductive rights, maternal health and what God has to say about the wellbeing of Black women.”

Chris Marks, a member of the Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Inc., was among the group of men in attendance to support women empowerment.

“I’m here to talk about premature births and women’s rights,” Marks said. “In our Black community, we are faced with the silent killer. Everybody in this community knows somebody who has been affected by premature birth and the complications of premature birth in a Black community is very heavy. First, we’re talking about infant mortality, time, depression and postpartum depression.

“So we’re out here to advocate for women’s rights. One of the bills that will be coming up in the Texas Legislature, hopefully, we’ll be able to understand the task force that will be studying the effects of premature birth on Black women itself. So I’m here to advocate for that. I’m here to let you know that men are part of the journey of fighting for women’s rights, with women’s rights and together we can get it done.”

Ayers explained it was important to have these types of conversations in the Black church.

“This is a conversation and a topic that we have not discussed particularly in the Black church,” Ayers said. “Here at Friendship-West, because we believe in justice for all people, we want to have this conversation and a very open dialogue around reproductive rights as well as maternal mortality and maternal care.”

Afterward, two women shared their stories of having trouble conceiving and how the medical community failed to provide them with the whole care they needed, even after labor and delivery. The stories were told as part of a prerecorded video presentation.

Ayers then asked Session why it’s important for women to have these conversations.

“As a womanist preacher and practitioner, this subject is very important to me and to womanists everywhere,” Session said. “One of the tenets of womanism is that we are concerned about the survival, the wholeness, the wellness, the thriving of entire people – male and female.”

She said the discussion was in line with her beliefs as well as her ministry and its work. She recalled Micah 6:8, “So it says God has told you Oh, mortal, oh, human, what is good? And what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?”

“And so, I began thinking about – and I want us to think about – what is justice? Justice is a primary attribute of God. It is maintaining the right relationship to the poor and the destitute. It’s rescuing the weak and the needy and delivering them from the hand of the wicked or the oppressed.”

She said there is a Hebrew term to describe justice. The word is Misphat, meaning to create or maintain equitable, fair and harmonious social relationships. She interpreted it to mean that all humans are made in God’s images and are therefore intitled to the same inalienable rights – to wealth, health and freedom – and no group is better or deserves more than any other.

“Unfortunately, there is more than enough research that reveals significant disparities in Black women’s wellness,” she continued. “Black women have the highest rates of poverty. They earn 63 cents for every dollar that a White man makes. Nearly 20% of Black women have no health insurance, and they die four times as often as White women from pregnancy related causes regardless of their income or educational status. So as a people of faith, if we are to be taken seriously, then we would know that we have a responsibility to do justice. That is to do whatever we can to level the playing field so that every human being, including Black women, have opportunities to experience wellness.”

Session said the reality is that Black women’s issues have been ignored.

“The sad truth is the church has historically been derelict in supporting and advocating for administering in ways that promote Black women’s comprehensive wellness,” Session said. “Reproductive justice is about doing just that. Because U.S. health care systems failed to address racial and gender health disparities. The term reproductive justice was coined by 12 Black women in June of 1994. It combines two phrases: reproductive rights and social justice.

“Reproductive justice is a strategy for taking on all the systems that harm and oppress Black women. It is not just about a woman’s right to terminate her pregnancy. That is the misnomer that we have. If we really dug into our history, we would know that many an enslaved woman in order to save their children from growing up in slavery as a form of resistance, put her child aside, and that’s a phrase that can be understood as terminating her pregnancy. So, when we think about doing justice, what I want us to understand is that it is so much deeper. So much nuance that we have been thinking about when we think about Black women, and we think about our health care and our wellness.”

Ayers then asked Jones what was considered reproductive rights for women.

“When we talk about reproductive justice – and also thank you for lifting how these terms have just been misused – it seems a little bit more palatable when you say reproductive justice instead of saying abortion,” Jones said. “But that’s not what it is. It is but it’s not. It is making sure that folks have the right to parent and just not women. It is whoever decides that they’re going to get pregnant, no matter what label that you have put on their name, that they have the right to parent with reproductive justice.

“It means that you have full bodily autonomy to parent in a way that you want to guarantee. It means that as two men or two women to non-binary or to whoever it is three or four; they have the rights of family. But they don’t only have the right to family, they have the right to family with the resources that they need that enables them to family and that means equitable access to health care. Not just equal access, but equitable access, because a lot of folks can fill out facts like health care, but they can’t afford to pay for it. It can come out of your paycheck, but they can’t afford to pay the copay to go to the doctor or the medicine, but having full access also means that you have the right to not parent if you choose not to. And you also have the right to have the resources to not parent. But if you so choose to parent, you have the right to parent in a way that is culturally sensitive to the way you parent, and you have the right to parent your children not being killed by state sanctioned violence. So reproductive justice is also a part of Black Lives Matter.”

Jones further explained how reproductive justice fits in with the movement.

“Yes, it is also a part of police brutality of the killing of Black folks and is also a part of the over criminalization of Black bodies,” Jones said. “Because when you take my son and my daughter, you take away my right to parent. Trayvon Martin’s mother was denied the rights of parents because her child was killed by state sanctioned violence. That is just how important reproductive justice is in making sure that everybody has the right to vote and have access to voting rights. Reproductive justice means that you are not supposed to be forced to live in environmentally unclean places where just the fact that the community that you’re living in, that child can be born with diseases and can be born with things that will go generation after generation.

“And then there is maternal mortality in a state like Texas, where your governor and all of his cronies have said that folks don’t have the right to make choices for their bodies, but in the same breath, he had the audacity to feel proud about passing legislation that allows for a woman to have six months of Medicaid when the data says she needs 12 months if she’s expected to live and her child is expected to live to decrease maternal mortality.”

She said it was like throwing a 6-foot rope to someone 12 feet away drowning in the ocean.

“I’m literally going to drown, I’m going to die,” she added. “So, you cannot force me to have a child and then not allow me to do things that I need in order for me and that child to survive. So that’s what reproductive justice is.”

Ayers followed up by asking Session what churches need to do.

“I would say take seriously the experiences of Black women,” Session said. “Listen to the women. Engage them in conversation.”

Willis, who also works as a doula, then shared her experience working at the center, as well as overcoming her own struggles to give birth.

“I started with just learning about maternal mortality and becoming a doula so I’m a full spectrum doula at Afiya,” Willis said. “I am also really fighting in advocating for young folks to be able to have the birth of their choice. Birth justice is really being able to advocate for people to birth with desired outcomes the way that they want to work in.… Being able to fight for those rights and bills and making sure those things are covered in fighting for expansion of Medicaid.”

Black women in Texas account for 31 percent of the deaths during or related to childbirth, but as few as 11 percent of live births, according to the Texas Department of Health and Human Services.

“I came to this work having gone through infertility and then having gone through stillbirth, having twin boys, and then ultimately having a daughter who was born prematurely at 26 weeks and then ultimately having a son,” McCormick said. “I saw multiple times the way health care fails Black women, and I was going through this experience when I was a graduate student.”

She went on to say that reproductive health issues touch every class, race and social status. However, Black woman are at greater risk to be denied proper care and/or access to it, because the system is not designed to protect them.

“When we think about the complexity of what it means to be a Black parent in this world, we cannot approach this through a kind of moralizing singular view, because we are a multifaceted people … As Fannie Lou Hamer tells us, ‘No one is free until everyone is free.’ And so we have to do that outreach.”

McCormick, who is writing her dissertation on Black female bodies and pain, reflected on the work of Dr. J. Marion Sim, known as the Father of American Gynecology. He was known for using enslaved women during his experimental surgeries without anesthesia to develop a treatment to repair the vaginal fistula. However, McCormick observed that in his writings about the experiments, he never talked about the women’s pain.

“Their voices are largely lost in the archive,” McCormick said. “But I was thinking about the fact that even in modern times when we think about the medical record, the same power holders are writing the record. And so those stories are still being lost in archive of all the stories we’ve seen and heard today. Those aren’t the ones that get treated with authority. And so this work is largely about that. And so, our first iteration we call it the livable Black Futures Storytelling Project, because we don’t want to just talk about the trauma, we want to talk about what it means to listen to Black Women and gender expansive people in envisioning the future. So, we are also shifting our attention to people who are formerly incarcerated to talk about carceral morality and state sanctions on people who are still in that kind of complex of Black bodies of property.”

One of the questions presented to the speakers was how Black women could safeguard their mental wellbeing. Session reiterated that, first, the church needs to listen to Black women. Then, she said, Black women need to listen to their bodies for signals.

“That means listening to our bodies, listening to our heart, emotional state. When we feel a certain way, when we feel burdened, when we feel like we have done too much, or we’re on our way to doing too much, listen to that and back up, take some rest. It’s okay to rest but listen. As a 62-year-old woman, it has taken me a very, very long time to learn how to even recognize what my body is telling me. That may involve being a part of a group [of] Black women of varying ages who can support one another, who can give you wisdom and insight and share some more storytelling and share their experiences with you.”

Willis also said sharing one’s story with other women could help as well.

“We are overcome by our testimony, and we are healed through our storytelling and so sharing our stories out loud, sharing it with people and sharing it out loud and trusting our bodies even as we get older can be really healing,” she concluded.