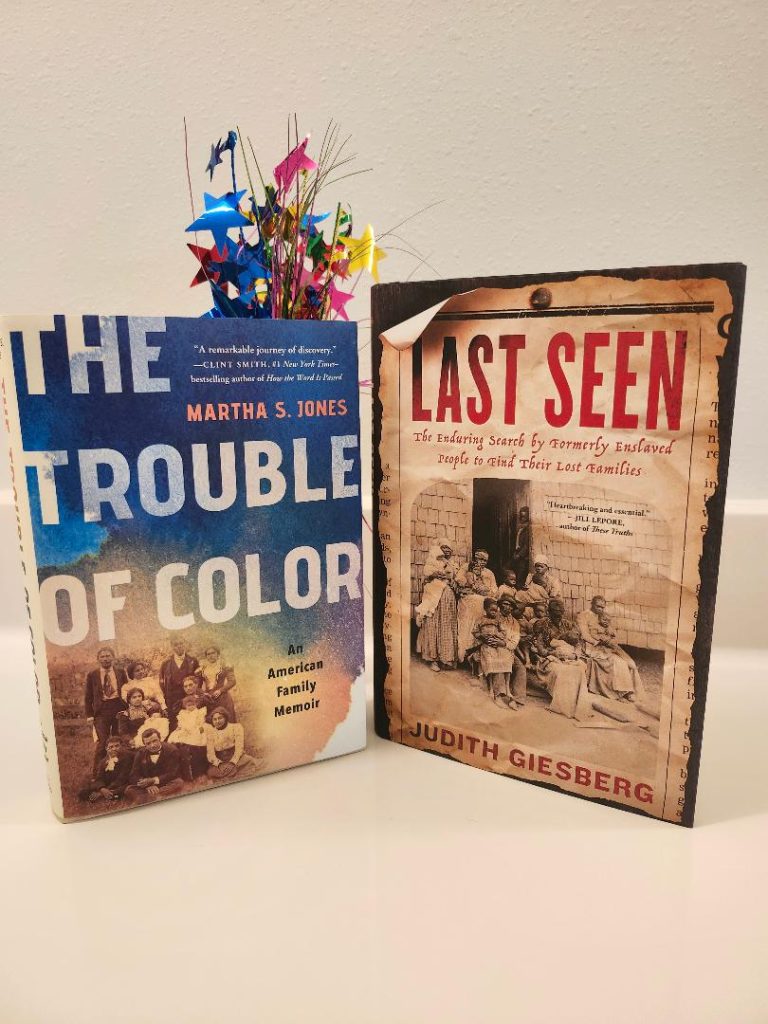

“The Trouble of Color: An American Family Memoir” by Martha S. Jones

c.2025, Basic Books $30 315 pages

“Last Seen: The Enduring Search by Formerly Enslaved People to Find Their Lost Families” by Judith Giesberg

c.2025, Simon & Schuster $29.99 309 pages

Who do you think you are?

That’s a question that can be taken a multiple of ways. It’s in-your-face, aggressive, angry. Or it’s inquisitive and open, asking for introspection. Where did your family come from, and who do you think you are? Or, as in these books, is that question to be answered?

For author Martha S. Jones, issues of identity were already understood: she’d grown up knowing that there were Black ancestors in her lineage, full-stop. She never thought it was anything but obvious – until a college classmate questioned Jones’ heritage.

In her book, “The Trouble of Color” (Basic Books, $30), Jones writes of untangling her truth. Color obviously mattered differently to Jones’ three-times-great grandmother than it did for her parents. Color didn’t draw a smooth line through history, it didn’t stay in one place or even in one century. The story of living as someone of color weaved all along Jones’ family tree, often revealing nuggets of pride, strength, and of surprise.

There’s a journey inside this book that begs readers to go along – and you’ll be glad you did. It takes you from city to country to find Jones’ ancestors, and it’s both comfortingly familiar and quite astounding. If you’ve ever delved into your own heritage, had your DNA tested, or looked into your ancestry and discovered unexpected things, this is a book to read.

If you’ve done those things, then you know the delight you feel when you found someone who was lost – and you’ll understand the heavy sadness and urgency inside the stories in “Last Seen: The Enduring Search by Formerly Enslaved People to Find Their Lost Families” by Judith Giesberg (Simon & Schuster, $29.99).

One of the most heinous practices of slave-owners in America was the separating of families. Children could, and were, sold away from their parents. Siblings were divided. Husbands and wives were sold apart, with no idea if or when they might see one another again. After Emancipation, it was common to see advertisements in newspapers, classified ads, editorials, and posters in search of missing loved ones and separated relatives.

In this heart-wrenching, sometimes happy, always powerful book, Geisberg profiles a tiny handful of those stories. Once he found them, for instance, Tally Miller changed his surname so that no one could ever take his family away from him again. Hagar Outlaw struggled to find as many of her nine children as she could, once she was freed. Time never stopped husbands from looking for their wives (or the other way around), or siblings from finding each other.

This book explodes the imagination, and it’ll make you glad for the research methods we have at our disposal today. Readers who’ve hit a dead-end on their own genealogical searches will want to read this important slice of devastating American history.

Of course, these books will make you want more, and you’ll get it by heading for your favorite bookstore or library. There, you’ll find what you need, and who maybe you think you are.