CHENNAI, India — “Fellow parents at my daughter’s school are already making plans on what [education] stream their children will choose,” Sapna Raghu, 35, a Chennai-based mom to a first-grader, told Zenger News.

“What’s the guarantee that jobs in those streams will be ready for them when they graduate?”

Schooling in India — home to the largest young population — is about choices. But more often than not the choices are between science and humanities, and most children end up with science. No wonder that of the approximately 7.5 million science and engineering graduates in the world, one-fourth are from India, according to a National Science Foundations report.

This has been the norm for generations. The education board that most children in India opt for — the Central Board of Secondary Education — evaluates students based on their ability to memorize subjects rather than skill development, knowledge application, and encouraging innovation.

But increasingly, parents, students, and educators are acknowledging that embracing the symbiotic relationship between science and the arts is the right way forward.

To enhance this, storytellers and publishers in India are putting together books around STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts, and Mathematics), which seeks to make STEM education stronger by encouraging creative critical thinking. Because the jobs of tomorrow will require imagination and innovation.

This intersection of science and arts in the literary field in India is not new — “Runaway Cyclone”, authored by Jagadish Chandra Bose in 1896, is touted as one of the first Indian sci-fi writing. This genre has been easily accessible to adults, too.

But it’s only in recent years that it has filtered down to early readers aged five and above, whose attention span is in minutes.

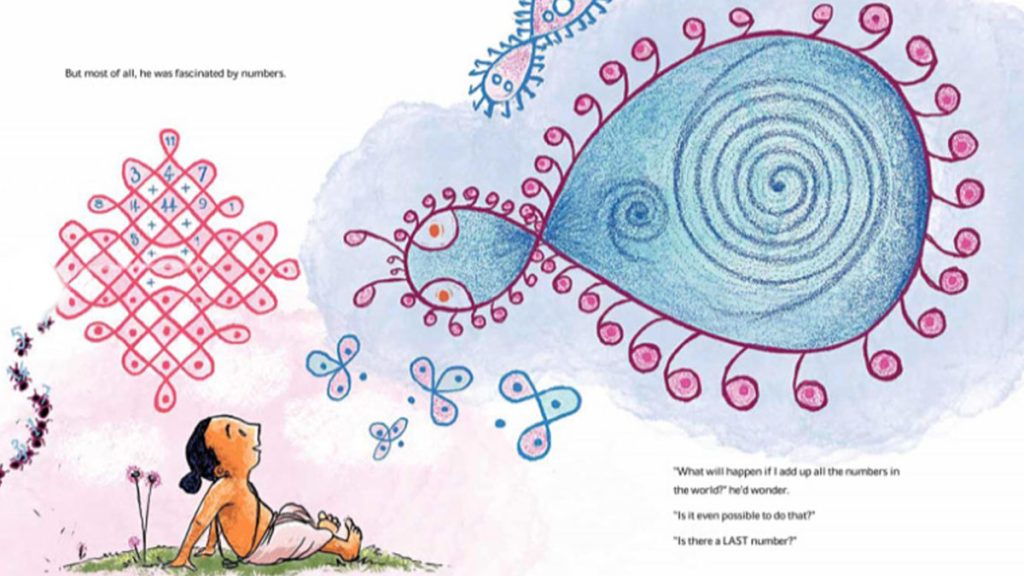

Last year, Priya Narayanan’s “Srinivasa Ramanujan: Friend Of Numbers” — which tells the story of genius Indian mathematician Ramanujan — was the Neev Book Award Winner in the ‘Emerging Readers’ category. The book was published by Tulika Books.

“Introduction to Coding – Scratch Your Brain and Crack” by Dreamland Publications is another book that came out recently and has become a bestseller.

The narration of these books is far removed from the phraseology of a textbook. They look like a story, read like a story, and feel like a storybook. The illustrations are colorful and playful keeping in mind its target audience.

“Fly in Space” by Aashima Freidog, is one such book that has been inspired by the space adventures of fruit-flies. Freidog has woven a story around the ‘eureka’ moment behind the decision to study fruit-flies as the first animals in space while couching it in a fun, relatable narration with quirky illustrations for support.

Freidog, who is the founder of The Life of Science which is a media platform focussing on femme voices in Indian science, has seen several instances of art and science intersecting through her work. But she “doesn’t see the same reflected in science instruction at schools”.

In stories for young readers, technology is never presented for technology’s sake. It is narrated with context and empathy like in Riddhi Dastidar’s “Neelu and the Phenomenal Printer”. A tale on 3D printing technology and how it can change and better the lives of animals with missing limbs.

Dastidar’s career path is emblematic of this fluidity of science and arts. She has a Bachelor’s in Molecular Biology, a Master’s in Gender Studies, and is a reporter and writer on psychosocial disability, gender, and human rights.

“What I learned in school with respect to science was usually run-of-the-mill stuff,” Dastidar told Zenger News. “These days textbooks have improved.” As a teacher, Dastidar has seen textbooks approaching scientific and technological aspects with context and relatability. But she’s certain that more needs to be done in terms of dismissing the perception that science belongs in the lab.

Gone are the days when Engineering and Medicine were the top career choices. Today, we have Artificial Intelligence creating art, apps that write. It’s increasingly becoming evident that you need to be adept at and open to both [educational] streams.

This is where Sudeshna Shome Ghosh of Bangalore-based Cosy Nook Library believes the library comes to the rescue.

“Kids have a lot of autonomy on what they can pick up and what they can read,” Ghosh told Zenger News. “There is much less judgment here. At a book store, they ask parents to buy them a book. Then they have to answer questions such as why do you want that.”

The country’s publishers have taken note. “Over the past few years, we realized that there’s an interest from educators, librarians, and children for books that stoke curiosity,” said Bijal Vachharajani, senior editor at Pratham Books.

“They want to deep-dive into STEM subjects. They want to read STEM biographies and see what people can achieve. This indication came from the field, through our community libraries.”

The publication has been concentrating on STEM, STEAM catalogs since 2015.

Vachharajani says it’s too soon to answer if the Indian schooling system and society are fast amalgamating the arts and science, but she does believe that the readership of books such as Vidya Pradhan’s “Who Drives A Driverless Car?” and Sudipta Sengupta’s “The Rock Reader” are creating a space for “conversation around options that children can have as they grow up.”

(Edited by Abinaya Vijayaraghavan and Amrita Das. Map by Urvashi Makwana.)

The post Bridging The Art & Science Gap: India’s Kids Reading Stories That Teach appeared first on Zenger News.