By Clint Confehr

NASHVILLE, TN — An upcoming celebration of abolitionist clergyman Absalom Jones at Christ Church Cathedral will be followed by a reception including a picture of the court trial from Columbia’s 1946 race riot.

The 6 p.m., Sunday, Feb. 11, worship service across Broadway from the Kefauver Federal Building is set by the Beloved Community of Tennessee’s Episcopal Diocese as commissioned by its bishop, the Right Rev. John C. Bauerschmidt, to advance racial reconciliation.

“We do not live in a post-racial society,” said Cumberland University Adjunct Professor Bill Gittens, cochair of the commission. “Part of our work on racial reconciliation is for white people to understand the nature and scope of white privilege and how it affects their daily lives, conscience and unconscious, and how the sin of racism affects the oppressor as well as the oppressed.”

As white privilege and the sin of racism “are two sides of the same coin,” Gittens said, “acknowledgment of those truths is what begins the process of racial healing.”

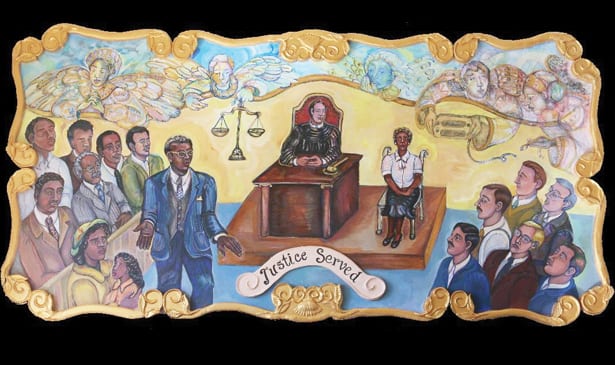

Racial healing is a goal for retired Martin Methodist College art teacher Bernice Davidson. Her interpretive folk art painting, “Justice Served,” portrays legendary Nashville-based Civil Rights lawyer Z. Alexander Looby, his clients and others at risk of lynching after Columbia’s race riot. It started when a Navy veteran defended his mother because she was cheated by a radio repairman at Castner Knott.

reconciliation. Photo by Clint Confehr

“Justice Served” will be on display in the Cathedral’s Parrish Hall after worship services including a sermon by the Rev. Naomi Tutu of Christ Church.

Tutu has spoken of reconciliation because of her experience in South Africa and learning about racial reconciliation from her father, South African Anglican clergyman Desmond Tutu, after Apartheid, says Natasha Dean, another Beloved Community cochair.

In 1792, Absalom Jones and other blacks walked out of St. George’s Methodist Church, Philadelphia, protesting segregation of the eucharist. In 1794, an African Episcopal church opened in Philadelphia and Jones became its deacon in 1795 and, in 1804, the first African-American Episcopal priest.

“You can’t have racial reconciliation without the requisite truth telling,” Gittens said, anticipating the service, then turning to Davidson’s painting. “This painting is a vehicle for truth telling.”

Unveiled Dec. 8 in Lawrence County’s courthouse, the interpretive folk art painting portrays a trial moved there from Maury County’s courthouse.

During the Feb. 11 reception, Davidson is to stand with Bridget Stuart of Spring Hill, a cousin of James “Steve” Stephenson. His defense of his mother — Gladys Stephenson was cheated by an employee of Castner Knott’s store in Columbia — led to a riot after the employee hit the back of the veteran’s head. The fight spilled into the street and grew.

“That whole history needs to be told and recognized because of the events occurring today,” Gittens said of “renewed emphasis on white nationalism.”

Deane says the trial “was an averted lynching … but many were arrested” after the riot. Looby was part of the changing time when lynching was seen as justice to a period where justice is in a courtroom where truth is established.

“We never got all the way to justice,” Deane said. “The reason we are experiencing resonance with this now is because in the current day — in this period of mass incarceration — justice for many African Americans is not being served and many believe we are going back.” Too often, people participate “in a miscarriage of justice, not just the fringe people” such as demonstrators at Charlottesville, Va. Reconciliation is important because “the middle can be complicit … The 1946 behavior in Columbia was normalized. White supremacy was a big part of it.”

People still suffer from Jim Crow segregation and lingering ill will, according to discussion among 150-175 people after “Justice Served” was unveiled in Lawrenceburg, permanent home for the painting.