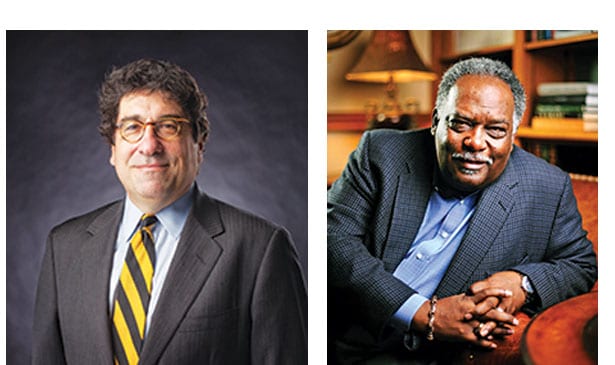

By Nicholas S. Zeppos, Chancellor, Vanderbilt University and David Williams, Vice Chancellor for Athletics and University Affairs and Athletics Director, Vanderbilt University

Reconcile. It is a word that weighs heavily in the history between Vanderbilt and a young African American man who had the courage to leave the relative safety of his North Nashville neighborhood to attend the university on a basketball scholarship in 1966.

After being recruited by legendary basketball coach Roy Skinner, with the support of then-Chancellor Alexander Heard, Perry Wallace was among the university’s first African American students.

He had been heavily recruited by coaches at northern, white universities as well as historically black universities, like Tennessee State University, that were athletics powerhouses. He has said he chose Vanderbilt, in part, because of the respect Coach Skinner showed his parents – addressing them as “Mr. and Mrs. Wallace” – an uncommon gesture in 1966 and something none of the other recruiters from white universities had done.

Arriving at Vanderbilt in 1966, Mr. Wallace had gone from the nurturing environment at North Nashville’s Pearl High School, that for 50 years was the city’s only black high school and a source of academic and athletic pride for Nashville’s black community, to an environment that was decidedly hostile.

Vanderbilt then was like much of the nation – many on campus had reconciled their beliefs with the doctrine of separate but “equal.” Those beliefs were evident in the isolation and maltreatment Mr. Wallace and his fellow African American students, including his best friend and Pearl High School classmate Walter Murray and another newly-recruited basketball teammate Godfrey Dillard, suffered on campus. Those beliefs underscored the prevailing thought of the time – that African Americans had no place at an institution like Vanderbilt, including on the same basketball court as white students.

That first year, Mr. Wallace and Mr. Dillard, as members of the freshman basketball team, had the added challenge of facing terrifying abuse and hatred on the road from fans throughout the South.

While the two of them had made history as Vanderbilt’s and the Southeastern Conference’s first African American basketball players, only Mr. Wallace would make the university’s varsity team. It is widely believed that Mr. Dillard, who had been a leading scorer as a freshman and had recovered from injury, did not make the varsity team because his aggressive style of play and political activism on campus – he founded the Afro-American Student Association and was a vocal advocate for his fellow African American students – was unwelcome at the university.

In December 1967, Mr. Wallace made history at Vanderbilt’s Memorial Gym as the first African American scholarship athlete to play varsity basketball in the SEC.

Vanderbilt is marking the 50th anniversary of that historic basketball season and recognizing the legacies of Mr. Wallace and Mr. Dillard with a series of activities and events this academic year, including a documentary film, Triumph: The Untold Story of Perry Wallace. On Dec. 2, the SEC will present both with the SEC’s Michael L. Slive Distinguished Service Award. Together, Mr. Wallace and Mr. Dillard forever changed Vanderbilt, the SEC and our nation.

Indeed, Mr. Wallace, Mr. Dillard and their fellow trailblazers had myriad experiences during their time at Vanderbilt – from isolation and fear to moments of understanding and achievement.

However, for many years after their time at Vanderbilt, the need for the university, Mr. Wallace and Mr. Dillard to acknowledge their shared past – to reconcile – was unfulfilled.

Even, as Vanderbilt welcomed its most diverse class in history this year, we recognize that widening the door is not enough. It is imperative that we create a community where all feel welcome, where diversity is celebrated and sustained. As we move forward to build a more inclusive and diverse community of excellence, this journey requires a critical look at the Vanderbilt of the past. Mr. Wallace, Mr. Dillard and their fellow pioneers are inextricably linked to both.

Fortunately, we’ve reconciled with Mr. Wallace and Mr. Dillard – and worked to honor them in many ways, from awards and an engineering scholarship named for Mr. Wallace to asking them share their stories with today’s Vanderbilt students as not only as lessons in courage, equity and inclusion, but also of resiliency in the face of incredible odds. Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collison of Race and Sports in the South, The New York Times best selling book written by Vanderbilt alumnus Andrew Maraniss and that chronicles Mr. Wallace’s and Mr. Dillard’s experiences, has been required reading for all incoming first-year students for the past two years.

Reconcile. It has the potential to either divide or unite. As individuals, we have the unsettling ability to reconcile within ourselves beliefs to justify actions that can cause harm to others. At the same time, we have a great ability and opportunity to restore relationships with those who have been harmed or mistreated so that we may achieve reconciliation.

At Vanderbilt, we are choosing the latter – to chart a path ever forward toward a more perfect union with healing, justice, empathy, passion and insight.