By Priscilla Thompson

ALAMO, TX — Along the winding Rio Grande in South Texas lies a history many have never heard, of a southern route to freedom for enslaved people on the Underground Railroad into Mexico.

“It’s so close, but yet it was so far for so many people,” O.J. Trevino said, peering across the river at the Mexican side of the border from his family’s property. “Knowing that they just had to get there.”

Trevino, who grew up just 5 miles from the border, was shocked to learn that his fifth-great-grandmother helped ferry escapees across that river to freedom.

“I come from a Mexican family, but then to understand, she was formerly enslaved. They helped other people that were enslaved into freedom,” he said. “It’s a sense of pride knowing that you had family that did that.”

Dubbed the “Harriet Tubman of Texas,” her name was Silvia Hector Webber.

Now, new research by María Esther Hammack, an assistant professor of African American history at Ohio State University, is shining a light on how Webber obtained freedom and her pivotal role in the Underground Railroad to the southern border. As the country marks Juneteenth — the moment on June 19, 1865, that the Union Army reached Galveston, Texas, to announce that slavery had been illegal — Webber’s life is at the center of an exhibit, “Freedom Papers: Evidence of Emancipation,” at the University of Texas at Austin’s Briscoe Center for American History.

Sofia Bravo, Webber’s sixth-generation great-grandchild and caretaker of the family’s land in Alamo, Texas, said this family history had largely been a secret until now. The discrimination both Latinos and Black residents faced kept that secret alive, she said.

“It wasn’t allowed for you to know that you were part of a Black family,” Bravo said. “Barely they accepted you as Hispanic; can you imagine if they found out that you were Black?”

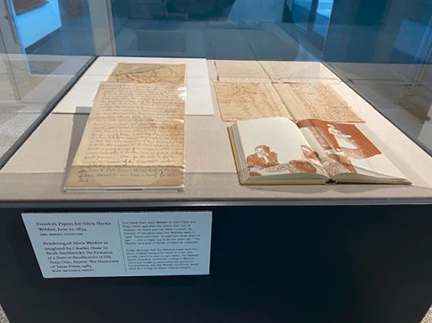

That fear has been replaced by pride after researchers discovered Webber’s “freedom papers” from the 1830s. The rare document, on display at the Briscoe Center, provides new insight about Webber and her husband, John, who was white.

“Silvia Hector Webber was a remarkable person,” exhibit curator Sarah Sonner said. “We know that her home offered a place of refuge on the path to freedom via Mexico for the Underground Railroad. We also know the steep price that she and John were asked to pay to achieve the freedom for Silvia and their three children.”

According to the document, Webber’s enslavers requested payment in the form of two children — not Webber’s own — “a negro girl three years of age … and a negro boy to be two years old.”

“In paying that they would have perpetuated the very system that they were attempting to escape,” Sonner said.

The Webbers never paid their bond, and instead, forfeited more than 800 acres of land near present-day Austin that they’d put up as collateral for the freedom of Webber and her three children.

In the decades that followed, they operated ranches along the Colorado River and the Rio Grande, researchers say, building ferry landings and offering safe passage to those moving toward freedom in Mexico.

“It shows just the fight that she had in her, just the not being satisfied in seeing the injustice that was going on and saying, ‘OK, we have to do something,’” Trevino said.

Webber’s descendants have since started the Webber Family Preservation Project to protect her legacy and help other descendants of enslaved people discover their history. The family’s uncovered history has also given them a newfound appreciation for Juneteenth.

“There was so much more than just physical harm that was done,” Trevino said. “The emotional damage that was done, the generational damage that was done, so having that understanding and learning the significance of what Juneteenth is and what it took to get there, for people to get there and have that appreciation.”

“It’s taken a whole new meaning and concept for me,” he said.