Washington DC– Former Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Alex Azar declared a COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE) in January 2020. In March 2020, Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Relief Act.

States got an additional 6.2% in federal Medicaid dollars and a 4.34% increase for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). HHS administers the CHIP program that provides matching funds to states for health insurance to families with children.

“We had lots of people losing jobs and businesses closing down. And this is very common. When we have a recession the federal government provides more Medicaid funding,” said Joan Alker. She is Executive Director and Co-Founder of the Center for Children and Families (CCF), and a Research Professor at the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy.

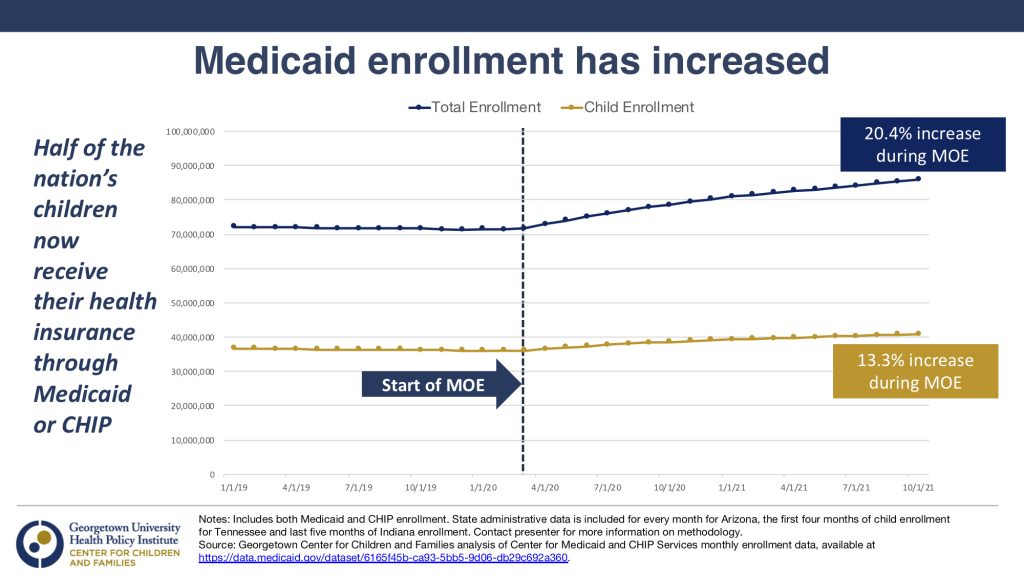

During the pandemic Medicaid enrollment has jumped 20%. (See graph.)

Alker said the increase in the federal government’s Medicaid share came with conditions. If states accepted the money, they could not rollback their eligibility levels for children and families.

She said states have done that in the past. “They would pocket the money but they would cut people off coverage,” she said. Tennessee has been one of those bad actors. If they take the federal money available during the COVID emergency, states can’t make it harder to enroll by raising premiums and once people were enrolled, they kept their medical coverage unless they chose to discontinue it.

“It’s taught us as a country that we can provide continuous coverage to our families and that’s really important at a time when families are struggling with rising food costs, with rising gas prices…. they don’t have to worry about large medical bills. We know that medical debt is generally the top cause of bankruptcy. So having that protection has been really valuable and I think it’s a lesson to be learned and the sliver lining of the pandemic,” Alker said.

According to the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University, 80 million people are currently insured through Medicaid or CHIP, about half of them children. Medicaid enrollment has increased under the relief act but an estimated 6.7 million kids will lose their insurance when the continuous coverage requirement expires. That is likely to happen sometime this year.

The PHE is in place until July 15, 2022. It will likely be extended another 90 days until October 15. States can reject the extra funding and Congress could act to lift the Medicaid continuous coverage protection on a certain date. The Biden administration said it would give states 60 days advance notice if they plan to lift the PHE.

When it ends, Medicaid enrollees are covered through the end of the month. Then, Medicaid Maintenance of Eligibility (MOE) requirements will resume and states will have 12 months to check eligibility for all 80 million people currently enrolled in Medicaid. Here’s the rub: extra funding will run out at the end of the fiscal quarter.

“Fourteen million people across the country are estimate to lose Medicaid coverage within a year after the emergency ends,” said Mayra Alvarez. She is President of The Children’s Partnership, a California nonprofit working on health and technology issues for underserved kids.

Alvarez said a drop in enrollment in Medical, California’s version of Medicaid, would disproportionately impact children of color who are more likely to rely on Medical for coverage. She said 75% of the more than five million children in Medical are kids of color.

“Even before the pandemic, long standing structurally racist policy and practices have created an environment where families of color experience a significantly greater degree of instability in everything from employment to income to housing. These economic and housing conditions are what heightens the risk of disruptions in health coverage and that eliminates the security that comes with having that coverage,” Alvarez said.

“Those first few years is when 90% of child brain development occurs, so that path for healthy childhood development depends on those frequent and timely well-child visits and screenings, “ she added.

Alvarez said that keeping kids covered is the right thing to do, so she and other health advocates are supporting AB2402, a bill that would “allow children enrolled in Medical to stay enrolled without making their families jump through administrative hurdles and keep them enrolled up to age 5.”

Last week the bill passed unanimously in the California Assembly Appropriations Committee. Next the full assembly will debate the bill and if it passes, it will move on to the California Senate.

“When 3 out 4 Medical children are children of color, we have an opportunity for our state to advance an antiracist approach to Medical enrollment one that removes barriers for families and gives every child a healthy start, beginning with ensuring that coverage is stable and continuous,” she said.

If AB2402 becomes law, every child enrolled in Medical could get 14 well-child visits before they turn 5.

“We know that when we combine disruptions with burdensome administrative requests to fill out forms and prove eligibility we risk disrupting that very coverage that keeps our kids able to get those critical screening, those supports, that care to grow up healthy and thrive.”

In case the bill doesn’t pass, Alvarez said advocates and the California Department of Health Care Services are informing parents that they may have to re-enroll in Medical when the public health emergency ends.