CANBERRA, Australia — Michael Goodwin remembers as if it was yesterday.

One of his history students, Nicole Sauer, in 2006, stood at the World War I grave of an ‘unknown soldier,’ one of the millions scattered across hundreds of commonwealth cemeteries on Western Front battlegrounds in Europe.

“You could see her head drop, and she started crying straight away,” he recalls.

After months of painstaking research through war records, the then 17-year-old from Mackay in north Queensland had managed to track down the final resting place of her great-great-uncle.

“It was just gold. You can’t put that into words,” Goodwin says.

“We’re talking about highlights-of-your-life kind of moments.”

Nicole’s investigations would see Lance Corporal James Launchbury given an inscribed headstone 100 years after he was killed in the quagmire of Flanders in 1917.

But now Goodwin fears future generations will be robbed of similar opportunities to connect with their history as the National Archives warns it’s on the brink of losing thousands of invaluable records and documents.

The agency that labels itself “the nation’s memory” has been forced to plead for public donations after thus far failing to convince the federal government to provide it with more funding.

Goodwin, who has taken almost 250 students on commemorative tours to Gallipoli and the Western Front, says losing the records would be devastating.

“I could talk forever about the wonderful responses that we’ve seen over the years … and all that comes back to the Archives,” he said.

“It’s the key to it all: by doing that research, the subject becomes a real person.”

The archives are legally required to collect and maintain government records, but aging materials, technological changes, and a lack of staff make the task nearly impossible.

Thousands of records — which include speeches given by World War II prime minister John Curtin, tapes from hearings of the Stolen Generations royal commission, and recordings of Indigenous language — urgently need to be digitized before the original materials are lost forever.

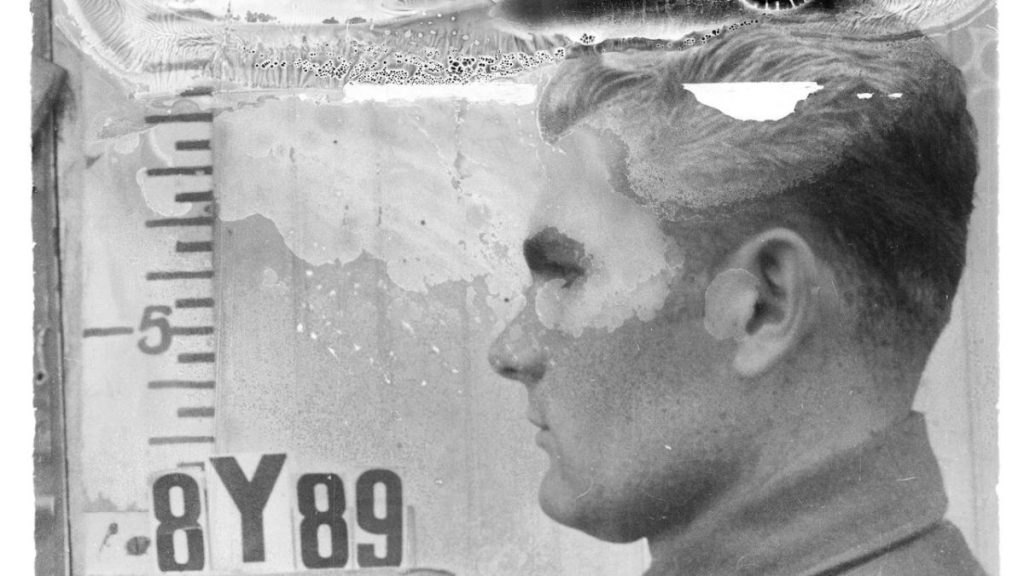

Like those of Italian prisoners-of-war housed in Western Australian camps, many films and photographs are captured on acetate film, which becomes brittle and shatters under any pressure.

Others are on magnetic tape or paper that has also started to deteriorate.

There are no backup copies.

National Archives director-general David Fricker claims that the agency has less than four years to save much of the vital material.

“If we lose that stuff, it’s like Australia gets amnesia,” Fricker said.

“We forget who we are, and we’re living on misinformation and whatever you can find on Google.”

A review of Archives’ operations handed to the federal government in January 2020 found the agency urgently needed AU$67.7 million ($52.2 million) to save under-threat records.

This month’s federal budget provided only a small boost to its operating budget and no allocation for extra staff.

As a result, the Archives have turned to taxpayers. In just over a week, about 250 people have signed on to be fee-paying members of the Archives, and about AU$30,000 ($23,162) has also been donated.

While the response has been overwhelming, there is no way the money needed to save all the records can be amassed through donations, Fricker warns.

Historian Jenny Hocking spent years locked in a high-profile legal battle with the Archives but is now among its staunchest defenders.

Professor Hocking won a High Court challenge against the agency’s refusal to give her access to correspondence between Buckingham Palace and Australia’s governor-general during the tumultuous months leading up to the dismissal of the Whitlam government in 1975.

It was a decision that cost the Archives almost AU$2 million ($1.5 million) in legal fees.

While she believes the money could have been better spent, Hockey claims that the Archives being forced to beg for public support is a “national disgrace.”

“It’s the appalling situation that our national repository is having to resort to a form of crowdfunding to try and protect some of the most significant documents in its holdings.

“It’s an absolutely humiliating spectacle.”

The work of historians would be impossible without the Archives, as per Hockey, labeling the agency’s treatment by the government as “cultural neglect.”

She is critical of the federal government’s misplaced priorities, citing the AU$500 million ($386 million) allocated to replace a 20-year-old building at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

While Fricker insists the war memorial deserves funding, he argues it wouldn’t exist without the Archives. No museums either.

“Everything we know would be not much more than mythology, really.”

Goodwin, Fricker, and Hocking all say it comes down to the old adage: those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.

“This evidence really is the only way that Australia can hold a mirror up to itself and have a good, honest look at who we are as a nation,” Fricker said.

“It really is irreplaceable and most precious stuff.”

(Edited by Vaibhav Vishwanath Pawar and Pallavi Mehra)

The post Australian Archives Crowdfunds To Save Vital Records appeared first on Zenger News.