By Ashley Benkarski

NASHVILLE, TN — When Rep. John Lewis, shown at right, began getting in “good trouble” in Nashville, he helped cement the city’’s place in the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement as the first Southern city to desegregate lunch counters.

An American Baptist College and Fisk University alum, Lewis took part in sit-ins along Fifth Street in 1960 and was among the original Freedom Riders who met the violent backlash of white supremacy a year later in Alabama.

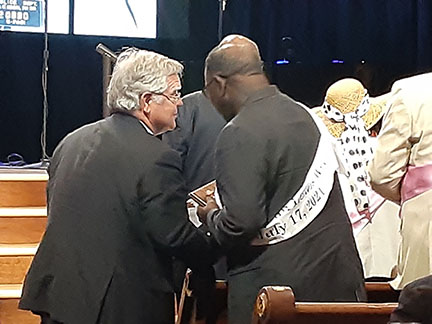

Rep. Lewis (D-GA) was honored with the official dedication of that same section of street in his name Friday and a Saturday morning march from that location to the Ryman Auditorium where a celebration of the Nashville student movement’s vanguard took place.

Former Vice President Al Gore, Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi and Representative Jim Cooper delivered remarks honoring the work of Rep. Lewis while Vanderbilt professor and presidential historian Jon Meacham recounted his time spent with the legendary activist as he worked on Lewis’s biography, titled “His Truth is Marching On.”

Dr. Catherine Burks-Brooks and Reverend James Lawson spoke about their experiences in those days of turmoil and persistence, recalling the constant viciousness of Birmingham Safety Commissioner Bull Connor, or as Dr. Burks-Brooks calls him, “that old Bull.”

Holding true to the idea of bearing witness against corruption, Rev. Lawson called on Gov. Bill Lee to acknowledge and repent for his role in the growth of the moral and spiritual rot of the state.

Deputy Mayor Brenda Haywood and Mayor John Cooper handed out keys to the city to Lewis’s family and the civil rights activists who put so much on the line for not just Nashville but all communities afflicted with racism by law.

Diane Nash, a Fisk student and fellow Freedom Rider, bestowed her key to local activist Justin Jones for his continuation of the movement’s virtues, including his role in the filing of federal litigation in 2015 against Tennessee for voter identification laws that restricted the voting rights of students.

Jones has been an advocate for the rights of the marginalized and underserved in the state and holds awards from the Tennessee Human Rights Commission, Fisk University Alumni Association, the Nashville chapter of the NAACP and ACLU-Tennessee, among others.

Images of Lewis in his tan trench coat at the fore of the 1965 march to Selma are iconic in the American mainstream as is the disturbing response of the city’s law enforcement. The state-sponsored beatings of marchers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge were meant to serve a cautionary lesson in history books, but as technology has given citizens nationwide the ability to capture such violence in real-time it has become clear the root of the problem has not been addressed.

Police brutality still plagues Black and Brown communities and the labor class at large, sparking the Black Lives Matter movement in 2014 and trending #SayTheirNames on social media. The voting rights progress Lewis worked tirelessly to protect and advance is now under threat, a possible response to the solidly-Republican Georgia voting for former vice president Joe Biden against incumbent Donald Trump last year and the wins of Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossof, both Democrats, to its Senate seats.

Thomas Coleman, 33, is a member of Gideon’s Army who works as a violence interrupter alongside engaging in community service and other volunteer work, including participating in the dedication. Clad in the same Lewis’ iconic trench coat, Coleman and colleagues from various grassroots justice groups marched the same streets as the late Civil Rights icon.

The weekend’s events were a learning experience that affected him a lot, he said, and Coleman felt good knowing he was continuing Lewis’s legacy of good trouble.