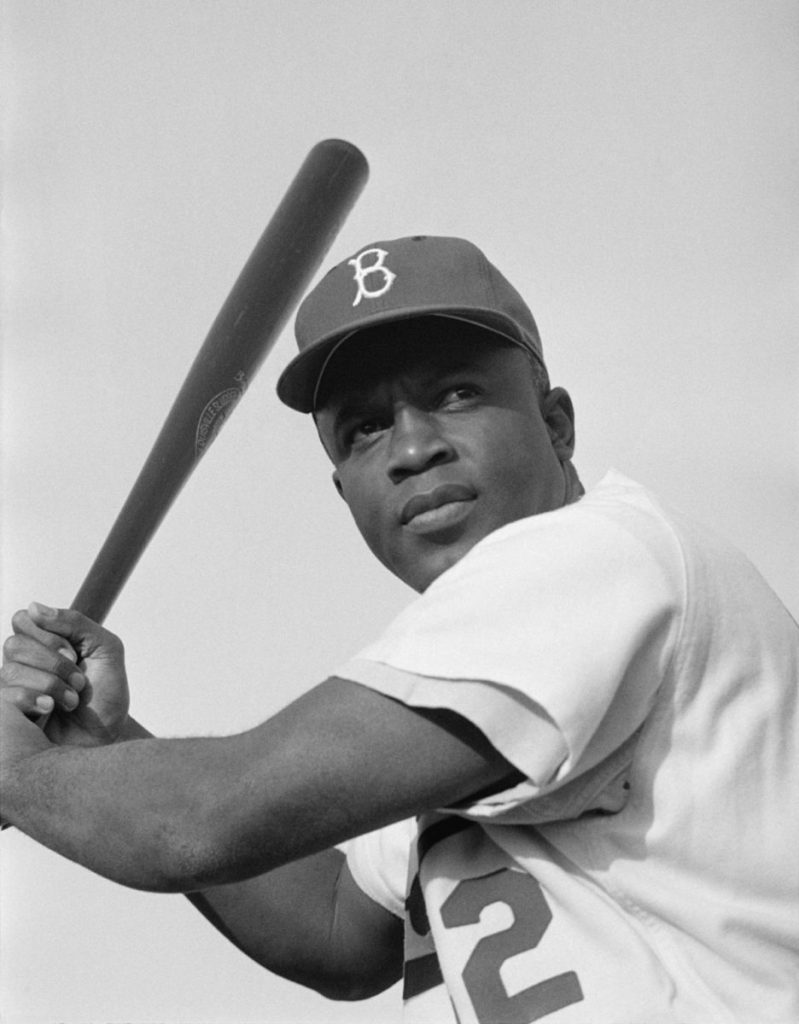

On this date, in 1947, the immortal Jackie Robinson stepped onto Ebbets field, then the home of the Brooklyn Dodgers. When he did so, Robinson broke the “color line,” becoming the first Black Major League baseball player since 1884.

Robinson was an exceptional athlete. He starred in football, basketball and track at UCLA in the early 1940s. Baseball was, if anything, a side hustle at the time. After serving in the Armed Forces from 1942 to 1944¹, Robinson played a season of Negro League baseball with the Kansas City Monarchs, where he came to the attention of Brooklyn Dodgers’ President Branch Rickey. When Rickey signed Robinson to a minor league contract in 1945, he wanted assurances from Robinson that he was prepared for the unimaginable vitriol he would face and that he would not retaliate. Rickey was interested in Robinson because Robinson could help the Dodgers win games. But he was also embarking on a historically consequential social experiment. And Rickey believed Jackie was the right man for both jobs.

Through his lone minor league season, in Montreal, in 1946, and his first two in the major leagues with Brooklyn, Jackie kept his promise to Rickey – no matter the provocation, Robinson held back. Through it all, he thrived. By the start of the 1949 season, Robinson had already established himself as an excellent player. And while he was still subject to vicious abuse, he was also a beloved icon, finishing second in a 1947 poll to Bing Crosby as the most admired man in America. He was also now among a cohort of a dozen or so Black Major Leaguers. At that point, Rickey and Robinson agreed the proverbial gloves could come off. If a player deliberately spiked Jackie or otherwise crossed a line, Jackie was free to fight back. Robinson responded by producing a stellar campaign in 1949. He won the Most Valuable Player Award as the best player in the National League and established himself as a superstar.

Robinson also became embroiled in the larger politics of the country in a way that would remain part of his public image for the rest of his life. In 1949, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), the notorious entity that hunted for subversives in American society, asked Robinson to testify against another Black icon, the singer and political activist, Paul Robeson. Robeson was a political radical, an outspoken critic of the injustices of the American system, including in its treatment of Black people. Earlier in 1949, he’d spoke to a Soviet-sponsored symposium in Paris. An Associated Press story misquoted him as saying that Black people could never join any armed American conflict against the Soviet Union, after which Robeson was vilified as an enemy of the United States.

Pledge your support

Robinson did not share Robeson’s politics. He grew up in a Republican household and remained one for most of his life. His parents gave him the middle name Roosevelt in honor of Teddy Roosevelt. But Robinson also knew that he was being used by HUAC to denounce Robeson because of his race. And Jackie was intimately familiar with some of America’s deficiencies. He told HUAC that if Robeson made the comments he did, that “sounded very silly to me” and rejected the notion that Robeson spoke for Black people in general. Otherwise, Robinson largely avoided taking the bait, telling HUAC:

“The fact that it is a Communist who denounces injustice in the courts, police brutality, and lynching when it happens doesn’t change the truth of his charges. Just because communists kick up a big fuss over racial discrimination when it suits their purposes, a lot of people try to pretend that the whole issue is a creation of communist imagination, but they’re not fooling anyone with this type of pretense, and talk about communists stirring up Negroes to protest only makes present misunderstanding worse than ever. Negroes were stirred up long before there was a Communist Party, and they’ll stay stirred up long after the party has disappeared unless Jim Crow has disappeared by then, as well.”

Robinson retired from baseball in 1956. and was elected into its Hall of Fame in 1962. He remained active in politics, including campaigning for Richard Nixon for President in 1960 against JFK, whose views on civil rights Robinson found weak and disingenuous. He later denounced Muhammad Ali for refusing to serve in the Vietnam War. He believed that promoting business opportunities would be a central source of uplift for Black folks. But as the 1960s wore on, Robinson’s one-time optimism about America’s future prospects for healing its racial wounds began to fade, and his views about the GOP soured. Robinson later recounted that the hatred he saw directed at Black people during the 1964 Republican National Convention in San Francisco, the year the GOP nominated Barry Goldwater, was among a “few nightmares which happened to me while I was awake.” In 1968, he refused to campaign for Richard Nixon, and instead supported the Democratic nominee, Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

Late in life, his regrets and bitterness multiplied. In a letter to his book agent in 1970, Robinson wrote:

“I once put my freedom into mothballs for a season, accepted humiliation and physical hurt and derision and threats to my family in order to do my bit to help make a lily white sport a truly American game. Many people approved of me for that kind of humility. For them, it was the appropriate posture for a black man.”

Pledge your support

“But when I straightened up my back so oppressors could no longer ride upon it, some of the same people said I was arrogant, argumentative and temperamental. What they call arrogant, I call confidence. What they call argumentative, I categorize as articulate. What they label temperamental, I cite as human.”

And in his memoir, I Never Had it Made, which came out in 1972, about a week after Jackie died at age 53, Robinson looked back at his historic role in integrating baseball:

Today as I look back on that opening game of my first world series, I must tell you that it was Mr. Rickey’s drama and that I was only a principal actor. As I write this twenty years later, I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made.

Robinson’s debut on this day in 1947 is an iconic moment in our history. I, for one, still get tearful watching and listening to recountings of that moment. Its aftermath, however, is too easily reduced to a smoothed over Hollywood ending imposed on the rough edges of a fraught and messy reality. It’s appropriate to honor Robinson not only for what he did in the 1940s and 1950s, but how he tried to make sense of it all looking back years later.

Thanks for reading Jonathan’s Quality Kvetching Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.