The NBA was a very different place in 1950. Not only wasn’t it viewed as one of the nation’s premier sporting attractions, but it was largely confined to the East Coast and completely  white. There was no NBA TV, very little national radio or TV coverage, no chartered flights or NBA players union, and neither any Black or foreign players.

white. There was no NBA TV, very little national radio or TV coverage, no chartered flights or NBA players union, and neither any Black or foreign players.

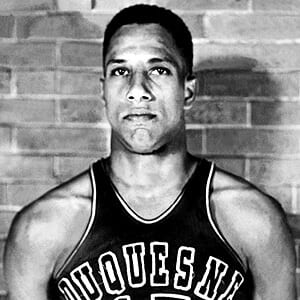

Chuck Cooper helped change all that. Cooper was a second-round pick of the Boston Celtics in the 1950 draft from Duquesne University. He’d already been a pioneer during his time there as well as being an All-American. Cooper was the first Black player to compete in a college game held below the Mason-Dixon Line. At six feet, five inches, no one was quite sure how Cooper would do in the pros, and even less certain whether he could navigate the obvious racial minefields that awaited him.

But Cooper played four years for the Celtics, for much of that time being Bob Cousy’s roommate. Cousy later said what he saw Cooper and other early Black players endure forever affected him, and gave him a full understanding of how much impact racism had on their lives. Cooper would later play with the Milwaukee Bucks and Fort Wayne Pistons before ending his basketball career as a member of the Harlem Magicians. He retired after suffering back injuries in a car accident.

Though his debut didn’t get anywhere near the attention given that of Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby in Major League Baseball, Chuck Cooper suffered considerable abuse. There was frequent and ugly racist taunting throughout his first couple of years, and several restaurants and hotels barred him. But Cooper’s perseverance led to other Black players being drafted, both on the Celtics and throughout the league.

Last week Chuck Cooper received a long overdue honor, one that should have occurred while he was alive to enjoy it. He was posthumously inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. His induction ceremony attracted many of the game’s greats, including former Celtics star and captain Bill Russell, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Julius Erving, Isiah Thomas and many others. His son told the Associated Press “It truly amazes me how the early African American pioneers played at such a high professional level while having to sacrifice, endure, and withstand the overt racism and social injustice of that time period.”

The NBA has certainly come a long way since those days. Today it is a global entity, having recently begun plans to establish a spin-off league in Africa, and having offices in Europe, Latin America and Asia. Players from a host of foreign nations are in the league, as witness what happened in the recent World Cup competition when an American team of pro players finished seventh, defeated by French and Serbian teams that also have NBA players.

However more importantly, there are Black coaches and general managers, as well as scouts, broadcasters, journalists, PR people and folks involved in every facet of the NBA’s operation. The draft is now only two rounds, but it gets widespread coverage. A number of former Celtics such as Russell, Sam and K.C. Jones and Satch Sanders have publicly talked about Cooper and how he helped make things easier for them when they were drafted.

Boston has long had a bad (and deserved) reputation in terms of race relations, but the Celtics have been an exception to that rule. They made Bill Russell the NBA’s first Black coach. They’ve subsequently had several others, and their reputation for being among the best organizations in professional sports when it comes to issues of diversity and inclusion dates back to the decision to draft Chuck Cooper.

Thankfully, he’s now in the Hall of Fame, something that should have happened decades ago.