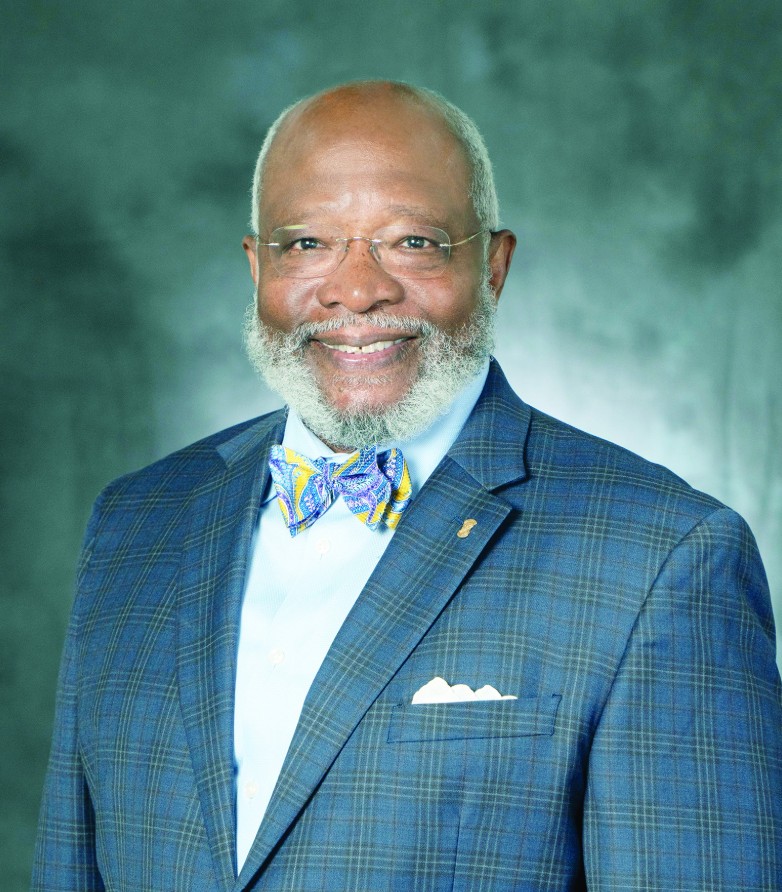

This is the first installment of a two-part series about Dale H. Long, who survived the 1963

bombing of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, AL.

Dale H. Long is known for telling stories — not fibs or lies, but the riveting truth of what

happened on September 15, 1963, just before 11 a.m., when a powerful bomb snuffed out the

lives of four little Black girls at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, AL.

Long was 12-years-old then and hanging out in the church’s library when the blast cratered the

east side of the church killing 11-year-old Carol Denise McNair and 14-year-olds Addie Mae

Collins, Cynthia Dionne Wesley and Carole Rosamond Robertson.

“There were about 10 of us in the library,” says Long, who along with his younger brother

Kenneth was dropped off at the church by their mother. “All of us were musicians. We should

have been getting ready to go upstairs and play in the church’s orchestra.”

It was Youth Sunday and Long was preparing to play his clarinet.

The library was in the church’s basement with a huge floor-to-ceiling bookcase. Long and his

friends were bantering about high school football — “boys’ stuff,” he says — when they felt the

room shake and noticed light bulbs exploding.

“I really didn’t hear anything [the bomb]. I could feel the percussion,” he says. “I knew something

was going on, but I wasn’t quite sure what it was.”

But then Long was compelled to run. “I remember running out of the library into the open area,”

he says, and fighting through dense smoke — including running into people and folding chairs.

“It was dark, dusty, smoky. It was hard to see where you were going,” he says, and remembers

hearing the wailing of fleeing church members.

Long finally made his way to the light in the stairwell. After ascending the stairs, he encountered

a mean-spirited police officer. “The police officer extended his arm to keep me from passing. He

told me, ‘Nigger, get back down there.’”

Long ignored the officer. He ducked underneath his arm and sped outside into an overcast day.

He could see birds hovering above the church while making his way to the corner of Sixth

Avenue and 16th Street.

The odor was pungent, he says, like the smell of gunpowder. Suddenly it dawned on him:

“They’re blowing up the church with people in it.”

People were milling around in a frenzy. Many were bleeding from shards of flying glass, he

says, and looking for their loved ones. Remembering his brother, he returned to the church and

ran into a fireman, who let him through.

Once inside, he searched the classroom, got down on the floor, looked under tables, and called

his brother’s name — Kenneth. No one was in the room, he says. So, he returned to the library

to retrieve his clarinet.

Long continued searching outside. “I finally saw this big oak tree that was in front of the church,”

he says. “It had grown up through the sidewalk. We used to play around that tree.”

A small group of children and a friend of his grandmother’s had gathered there out of harm’s

way — including Long’s brother, whom he offered to take care of until their father could get them

home.

“I hugged him and made sure he was okay,” he says. “He said he was.”

Copyright 2025 TNTRIBUNE. All rights reserved.