By V.S. Santoni

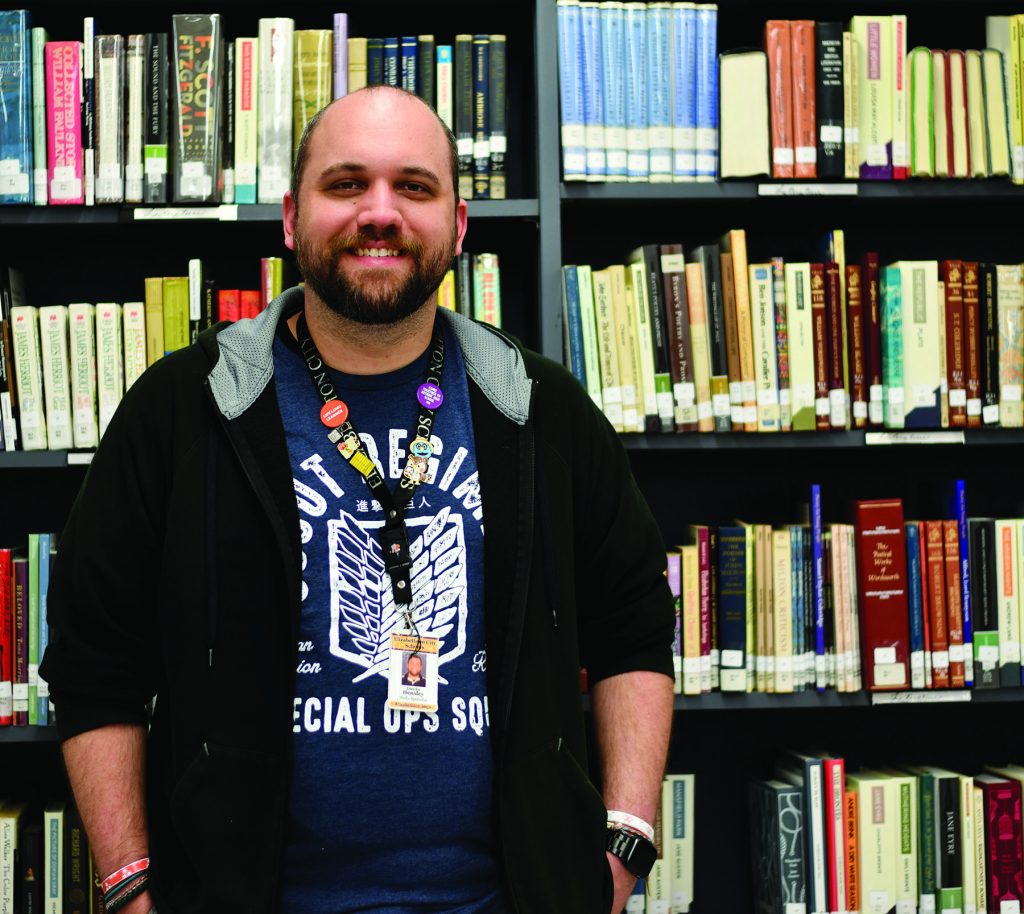

In 2022, McMinn County schools banned the Pulitzer-prize winning holocaust-themed novel, Maus. It was a move that provoked national headlines and led the Tennessee House of Representatives to pass a bill that would allow school boards to ban books deemed obscene. Under the current law, a parent, guardian, or teacher would launch a complaint about a particular title to their district’s super intendent, who would then assemble the school board to make a determination on whether the book should be banned. School librarian and recently-elected leader to the Tennessee Association of School Librarians Dustin Hensley said book bans like these put targets on librarians’ backs.

Hensley said book challenges lead to communities vilifying their librarians for the books on their shelves. Just last year, Louisiana residents Michael Lunsford and Ryan Thames ostracized middle-school librarian and 2021 School Librarian of the Year award-winner Amanda Jones online, claiming she was a pedophile grooming children. Jones took legal action against the two men, suing them for defamation, but Hensley notes such instances aren’t rare.

“That’s the big fear right now,” Hensley said. “. . . What will my community say about me if I have a book about a minority character or a character of a different sexual orientation?” Books centering Black characters and their experiences have been a favorite target. In 2017, Angie Thomas’ award-winning novel “The Hate U Give,” about a Black teenage girl who witnesses the murder of her best friend at the hands of a white cop, fell in eighth place on the American Library Association’s top ten challenged and banned books list.

“I have students in my school and in my library that are of different orientations and lifestyles. They need to see themselves reflected in the materials in our library,” said Hensley. “I won’t stop putting books on the shelf out of fear of retribution, but it’s something that will always live in my mind. I am active enough on social media that I could’ve, like other librarians, been attacked–I could easily be the next person.”

Hensley raised no objections to parents deciding what books their children should read, but when those parents take books off shelves, this deprives marginalized communities of representation. “We want our children to have the freedom to read,” Hensley said before explaining that book bans make marginalized children he has spoken to “feel like they’re under attack.” He continues that individuals need to trust the training librarians receive to curate collections that serve the needs of an entire community, not only a small segment.

“Actively voice support for school libraries and librarians,” Hensley requests of communities invested in the struggle for representation. To combat the vitriol, Hensley hopes supporters will bring forward positive stories about the role libraries play in shaping young people’s lives and the importance of allowing children to freely read according to their interests.