MEMPHIS, TN — On New Year’s Day 1992, a Memphis minister brought his two young sons to the brand-new Pyramid on the Mississippi River.

Bishop William Young and his sons, 12-year-old Paul and 8-year-old David, weren’t there to hear music or watch basketball. They went to the Pyramid with about 15,000 other people to see Dr. Willie W. Herenton sworn in as the city’s 61st mayor — and first elected Black mayor.

“My dad was so proud,” says Paul. “Proud to see a Black man become mayor, a man he knew and had respect for, a man he knew from the neighborhood. He wanted his sons to see that. I didn’t know or understand the gravity of the mayor’s role at the time, but being there showed me that great things are possible.”

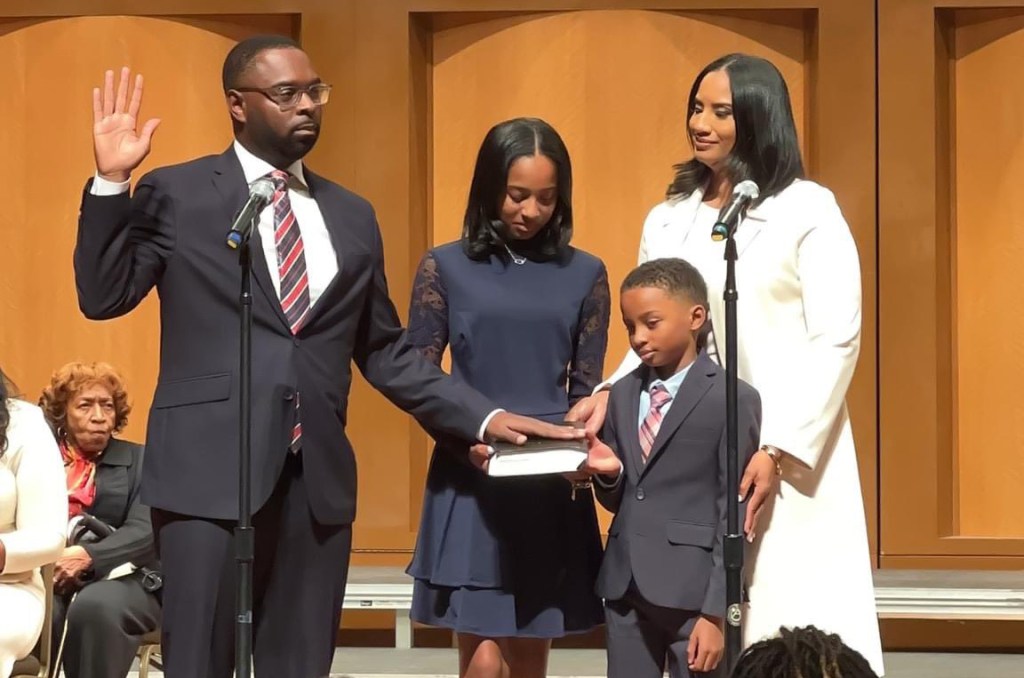

The gravity of the mayor’s role has come into focus for Paul Young. On New Year’s Day 2024, he was sworn in as the 65th mayor of Memphis. In the speech he talked about the transformation he hopes to lead as mayor, “a transformation that’s going to take us from hopelessness to hopeful; from poverty to prosperity; from hurt to healed; from stalled to thriving.”

“Less than two years ago, I’m sure very few people in Memphis visualized Paul Young as the next mayor. Most people had never heard of him,” says Otis Sanford, the veteran Memphis journalist and political commentator. “He ran an effective campaign, the best one of all the candidates stressing his experience in city government, his family background, and his deep roots in Memphis.”

When Paul was seven, his father became the founding pastor of a church in Bolivar, Tennessee, where he had served as chaplain at Western State Mental Institute. And when Paul was 11, his mother left the U.S. Postal Service to join his father as co-founding pastors of the Healing Center Full Gospel Baptist Church in Oakhaven.

“Our babies were drug babies for real,” says Paul’s mother, Dianne. “We drug them from one church thing to the next one.” The new congregation moved into the old Oakhaven Baptist Church and Academy. “We didn’t have that many folks,” she recalls. “We’ve never been a huge congregation, but we’ve always done huge things.”

The Youngs gave each of their children Biblical names. Dorcas, Paul’s older sister, was named for one of Jesus’ first followers, known for her “good works and acts of mercy.” Paul, the quiet middle child, was named for the first-century apostle who spread the teachings of Jesus. And David, Paul’s younger brother, was named for the shepherd who became a King of Israel and the “sweet psalmist” of Hebrew scripture.

“I’m still the smartest” Dorcas Young Griffin, director of the Division of Community Services for Shelby County, says with a laugh. “Paul’s more level-headed like Mom. I’m more fiery like Dad. When I started to drive, Dad wouldn’t let me go out by myself. I’d have to take Paul with me.”

“I think this is his calling,” Dianne says. “Being the mayor of Memphis for such a time as this, because it’s a tough time for the city. It’s a tough time, but Paul is prepared. I’m not worried that politics will change Paul. I think he’ll change politics in Memphis.”

“That’s what my mom said in her sermon,” Paul says. “God’s plan for your life will never be about you. It will be about helping others. And it was like, bam, that was it. It made me think. I thought about how my community looked and how I wanted to help change the neighborhood and the community. It was one of those bright-light moments.”

That moment sent Paul on a mission to find his mission. He found it in a University of Memphis graduate school catalog: A master’s degree in city and regional planning, promised the catalog, “prepares students for careers concerned with the physical development of communities, and the interaction of that development with the social, economic, and environmental well-being of communities.”

Paul enrolled in the program and got a job as a planner for the Memphis and Shelby County Division of Planning and Development.

“If I could have applied for the position of mayor and gone through a different process, I definitely would have,” Paul says. “I really don’t want to be a politician. I just want to do this job.”

Dr. Jamila Smith-Young, Paul’s wife of 16 years, also wishes he could have applied for the job instead of running for office. “Politics can be cruel, as we know,” she says. “Paul can handle that; we can handle that. But we agreed that we needed to make sure the children are protected and that our family time remains a priority.”

“Paul is not driven by power or ego,” says Smith-Young. “He’s driven by faith and family. That’s how he was raised and that’s how we’re raising our children.”

Young kicked off his campaign exactly one year before the election. Five days later, his father died of congestive heart failure.

On the night he was elected mayor, Paul thanked his family. He thanked his wife and children. He thanked his sister and brother. He thanked his mother and his wife’s parents. He thanked his father.

And he talked about the conversation he had with his father while trying to decide whether to run for mayor.

“He was asking me if I was going to run, and I said I don’t know because I know the weight of the job,” says. “I know what it means to be in that seat, and I just don’t know if we’re ready for that. My dad said, ‘I hear you, but Herman and Eva, your grandparents, they would never have imagined that their grandson would have the ability to even think about being the mayor of this amazing city. It’s not about you. It’s about what God has put in you for the rest of our city.’ Those words changed me.”