Columbia, S.C.–When James Terry Roach “started slitting his wrists after being convicted as a teenager, Dr. Green Neal had been the one to help ease his pain with medication. Now, the warden was strapping those familiar arms into the electric chair as the physician stood nearby,” Chiara Eisner wrote Wednesday for The State in Columbia, S.C.

“Dr. Green Neal has kept his execution experience secret for 37 years. But in March, the South Carolina Department of Corrections announced it was ready to start shooting the condemned to death with a firing squad — and that a doctor’s presence would again be required in the chamber.

The state’s first executions since 2011 were scheduled to occur on April 29 and May 13 but were temporarily put on hold by the S.C. Supreme Court last week. When they do happen, the doctor in the death chamber will again be a physician currently working for Corrections, not someone hired from outside, the agency confirmed.

“Neal has now decided to tell his story. He is only the second physician in recent history to talk in detail about his execution role with the press. . . .”The near-absence of such first-person accounts made the story “very rare and important for people to read,” Eisner told Journal-isms Friday. It was a responsibility she took “really seriously” because Neal had not told his family members or his patients about this part of his work.

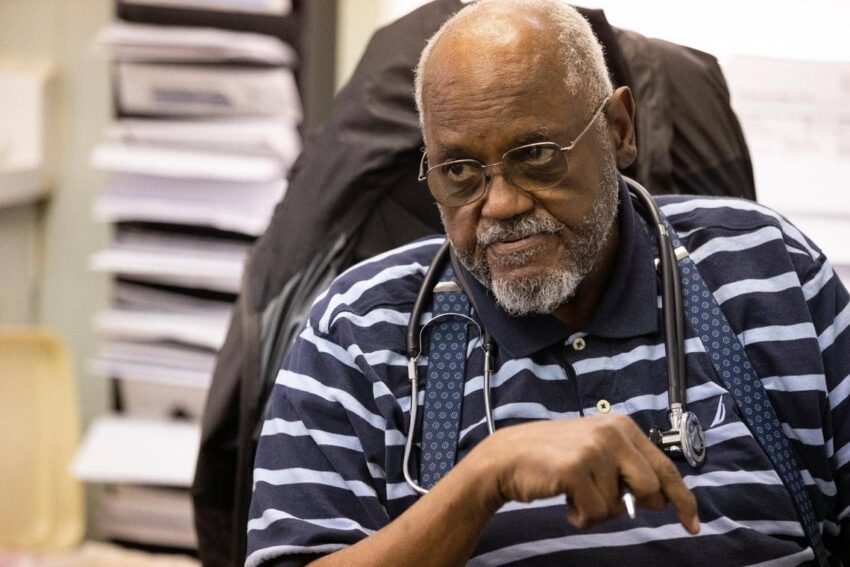

Neal, 76, is a Black internal medicine specialist who treats many who are older, low-income and dealing with multiple diseases. He told Journal-isms by phone Thursday that he decided to talk because “someone needs to know what the people go through.” Eisner has been writing about executions and execution workers.

A Meharry Medical School graduate, Neal left the execution business in 1996. After Eisner approached him, he said he checked out her journalism and talked with some of the sources in her stories. He was particularly impressed by “Cut Off,” about a majority-Black ZIP code where limbs were being amputated at an alarming rate. Eisner did not write the story, but helped promote it. About 70 percent of the death row inmates were Black while he was with the Corrections Department, Neal said.When Eisner wrote her story, she was sure to include the history behind that statistic: “For Black people in South Carolina, the state has long been a dangerous place. Before slavery was abolished, masters could kill the workers they owned and get away with it. After slavery was outlawed, the same thing happened under a different name. The state saw more lynchings of Black people per capita than most other places in the country.”

About 70 percent of the death row inmates were Black while he was with the Corrections Department, Neal said.When Eisner wrote her story, she was sure to include the history behind that statistic: “For Black people in South Carolina, the state has long been a dangerous place. Before slavery was abolished, masters could kill the workers they owned and get away with it. After slavery was outlawed, the same thing happened under a different name. The state saw more lynchings of Black people per capita than most other places in the country.”

But Eisner also focused on the ethical dilemma of a doctor who took an oath to “do no harm” yet is part of the state-sanctioned killing process.

“The silence of his peers is no accident,” the reporter wrote. “Doctors like him are stuck in a seemingly impossible predicament: They are required by state protocols to participate in executions even as they are prohibited by their profession from being involved.

“Across the country, physicians have been told to write prescriptions for drugs used in lethal injections, insert the needles that carry those drugs into people’s veins, and like Neal, inspect and pronounce people dead after the killing is done by other means, like the electric chair. “Each of those actions is considered unethical by national professional societies. The American Medical Association regards any official participation other than the signing of a death certificate as contrary to a doctor’s duty to heal and do no harm. The American College of Correctional Physicians is still more strict. It has stated prison doctors should not be involved in any aspect of the execution process.”

Neal contines to practice from an office that “could be confused with any small house in the city.”

During the executions, “While 2,300 volts of electricity jerked his patient around in the chair, he’d glue his eyes to the floor,” Eisner wrote. “Only after the nurse’s nod would he approach the body, feel for a pulse and listen for a long time through a stethoscope, waiting for the heart to finally stop beating. When the silence in his ears matched the stillness of the room, the doctor would send a nod of his own to the warden. He would sign the death certificate. Then, as the sun began to rise, he’d go straight home and tell nobody what he had done.”

His co-workers addressed their situations in their own ways. “There are other stories” that haven’t been told,” Neal told Journal-isms. Most decisively, “People quit their jobs.”(Photo of electric chair: South Carolina Department of Corrections)