By Ashley Benkarski

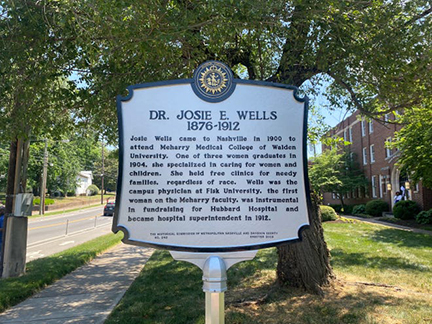

NASHVILLE, TN — 100 years after her death, the life and accomplishments of Dr. Josie English Wells will be cemented with a historical marker in her honor.

The unveiling took place last Friday in front of the former George W. Hubbard Hospital, with a reception following in the nearby Hulda Lyttle Hall Parlor and Meeting Space.

Sandra Parham, Executive Director of Meharry Medical College Library & Archives, with the assistance of Meharry Medical College CEO and President Dr. James E. K. Hildreth, submitted the application for Dr. Wells’s marker to the Metropolitan Historical Commission of Nashville and Davidson County last October.

“The energy was electric,” Parham described of the unveiling. Dr. Wells’s family even made it out to the event.

“‘You educate a man; you educate a man. You educate a woman; you educate generations,’” Parham, using the famous Brigham Young quote, said of Dr. Wells’s descendants, noting that she produced a lineage of medical professionals and business owners.

Her son-in-law, John T. Givens, is a famous Meharrian himself, and a scholarship in his name is given to a student annually in the School of Medicine, a testament to the impact of her family.

“There was so much enthusiasm, I didn’t even have to sell her story,” Parham said of the commission’s acceptance of the proposal.

Dr. Wells was born in Mississippi in 1876 to a freedman, Berry English, and his wife Eliza. She was the first of three women to graduate from Meharry with a medical degree in 1904. She was also the first female faculty member there and she opened the first private practice run by a female of any race in Nashville.

She met and married her husband, George Wells, a Latin professor at nearby Rust College in Holly Springs, Miss., but he died shortly after their only daughter, Alma Ninde Wells, was born in November 1896.

Now widowed and a single mother, Wells traveled from her Mississippi home to San Antonio, Texas, and from there to Nashville — All as a Black woman in the South during Jim Crow.

The hardships she faced and anxiety she endured over this new and tumultuous situation were insufficiently matched against her will to persevere, though, and she not only succeeded but thrived. “She crashed the glass ceiling,” Parham said.

Encouraged by Dr. G.J. Starnes, a Meharry graduate, to continue her efforts in the medical field, she traveled with Alma from Texas to Nashville and enrolled at the famed medical college, where she graduated in 1904.

Wells had worked closely with Dr. Starnes for years at his hospital and headed a nursing education program there.

For Parham, Dr. Wells’s determination to become a Meharrian is indicative of the importance of the institution itself. “It rings true of what Meharry meant to so many” because of Meharry’s foundation of altruism and spirituality, she said.

Once she made it to Nashville, she left an undeniable mark of humanitarianism on the city. She opened her private practice after graduation and ran a free clinic for indigent women and children weekly, regardless of race, and was a major fundraiser for her beloved institutions.

“Raising money for the new Hubbard Hospital was a huge undertaking, in which Wells was materially involved,” Parham is quoted as saying on the Meharry website. “When the hospital opened in 1910, Wells was its effective head, reporting to Hubbard, the medical school president and formal hospital superintendent. Although Wells became full superintendent in time, from the very beginning she, a Black woman, ‘had charge’ of the hospital.”

She was “widely involved in civic community work as part of the executive committee of the Colored Unit of the Women’s Council of Defense during World War I” and a fierce advocate for women, working with other Black women leaders during the suffragist movement, Meharry’s website states.

Dr. Wells served as Dr. George W. Hubbard’s administrative right-hand and became Hubbard Hospital’s first female superintendent in 1912.

Wells died March 20, 1921 at Hubbard Hospital from complications resulting from a goiter removal. She is buried in the historic Greenwood Cemetery.

Meharry, in a press release ahead of the unveiling, said her marker “will join those of noteworthy Meharrians, Hulda Margaret Lyttle and Donley Harold Turpin. Lyttle was a member of the first graduating class of Meharry’s Nursing School and Turpin was the Dean of Meharry’s Dental School in 1938 who gave his personal finances to the School to keep it afloat during the Great Depression.”

Parham said Meharry was a pioneer institution of its time and still is today, solidified in its future under the leadership of Dr. Hildreth.

For more on Dr. Josie E. Wells, visit https://home.mmc.edu under the “News & Events” tab.