By Lynn Norment

MEMPHIS, TN — Plans for a controversial crude oil pipeline through a Black Memphis neighborhood has stirred up protests, lawsuits, a call for help from the President of the United States and charges of environmental racism.

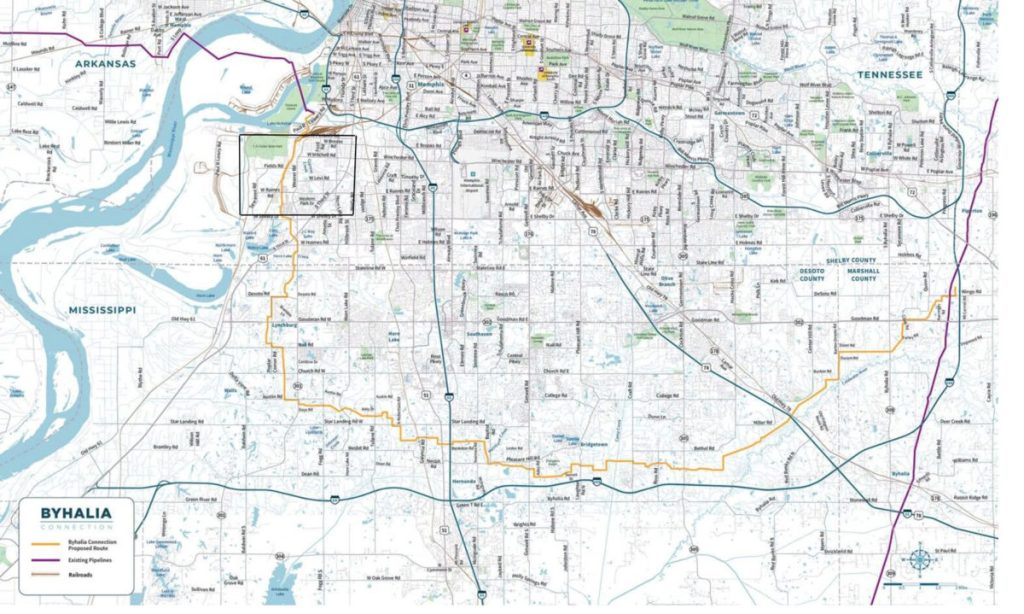

The 49-mile pipeline, a partnership between Valero Energy Corporation and Plains All American Pipeline, was set to run underground to connect a Valero refinery in Southwest Memphis to the company’s facility in Byhalia, Mississippi. It would connect to an existing pipeline that stretches from Illinois to the Louisiana Gulf Coast.

At least 7 miles of the pipeline would run through low-income, predominately Black neighborhoods in South Memphis that are already ladened with heavy polluting industries. One area is Boxtown, a community established by former slaves.

While some residents signed agreements allowing the pipeline to run through their property, others refused. The pipeline companies filed eminent domain cases, claiming they have the rights to the property of the Black landowners. The fight is now in the courts.

A representative for the pipeline said they chose the Southwest Memphis neighborhood because it was the “point of least resistance.” That statement outraged people. Kathy Robinson, Kizzy Jones and Justin J. Pearson, all with connections to the neighborhood, formed the Memphis Community

Against the Pipeline. They led protests and marches, and people across the city, county and country have joined the cause.

Robinson said those words, “point of least resistance,” infuriated her. Jones said they were a way for the companies to “threaten” and “bully” the neighborhood. “It’s racist,” she says.

Former Vice President Al Gore agrees. In a column in the Memphis Commercial Appeal newspaper, he wrote: “It is racist because the proposed route intentionally snakes through 97 percent Black communities of Southwest Memphis, where residents are already suffering a horribly disproportionate and dangerous level of pollution and a cancer rate four times the national average. It is a textbook example of environmental injustice.”

Gore, an environmental advocate known worldwide, also wrote: “Valero’s large refinery is already the worse source of toxic air pollution in Shelby County, with most of the pollution carried into Southwest Memphis. Last year, Valero spilled 800 gallons of crude oil near the planned route of the Byhalia Connection pipeline.”

The Southern Environmental Law Center notes that crude oil is known to contain cancer causing hazardous chemicals such as benzene, and the proposed pipeline would add to a long-standing pattern of allowing polluting companies to operate in Southwest Memphis. And with that comes enhanced health risks and environmental concerns, especially if there is a leak in the pipeline. Community leaders have said it is not a matter of “if” there is a leak, but “when.”

In addition to disrupting and endangering Black neighborhoods, the pipeline would run under the Memphis Sands Aquifer, which provides the city’s drinking water, and through the Memphis, Light, Gas & Water well field, where water is pumped from the aquifer.

In a lawsuit, three environmental advocacy groups _ the Tennessee Sierra Club, Protect our Aquifer and the Southern Environmental Law Center _ claim that the Army Corps of Engineers did not fulfill its requirements before granting a federal permit for the project.

National environmentalists are supporting efforts to stop the pipeline. In addition to Al Gore, other celebrities who have spoken out against the pipeline include Memphians Sybil Sheppard and Justin Timberlake as well as Danny Glover and Jane Fonda.

Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland as well as Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris both have expressed reservations against the pipeline and its potential risk to the city’s aquifer and drinking water and impact on the Black neighborhood. In addition, 28 members of Congress signed a letter asking President Joe Biden to stop the pipeline. The letter was written by Tennessee Congressman Steve Cohen, whose district includes the impacted neighborhoods.

In the coming weeks and months, this pipeline issue will continue to make headlines. It is a stark reminder that over the years Black neighborhoods across Tennessee and the country have been used as dumping grounds for toxic chemicals and other deadly industrial waste by major companies who show little regard and respect for our communities.

It harks back to the nine-year battle that Sheila Holt-Orsted and her family endured to get justice for the toxic dumping that poisoned the drinking wells of her family and neighbors in Dickson County, Tennessee. For at least three decades manufacturing companies in nearby Nashville had dumped industrial wastes containing industrial solvent trichloroethylene (TCE), a known carcinogen and reproductive and neurological toxin, at an unlined landfill adjacent to the Holt family property.

Over the years the family had been assured their water was safe, despite Holt-Orsted and her father both developing cancer in the early 2000s and her mother being diagnosed with cervical polyps. White residents in the area were warned of toxins in private wells and springs and quickly connected to city water many years earlier.

The settlement of Holt’s lawsuit provided the Holt family with financial compensation but also gave hope that the Dickson community would be permanently protected from toxic well water and provided with safe municipal drinking water.

It is encouraging that young people like Justin Pearson, just 26, are now fighting for environmental justice. As he has emerged as a leader in the fight against the Byhalia Connection Pipeline, he describes himself as “dedicated to justice–environmentally, socially, politically and economically.”