By Reginald Stuart

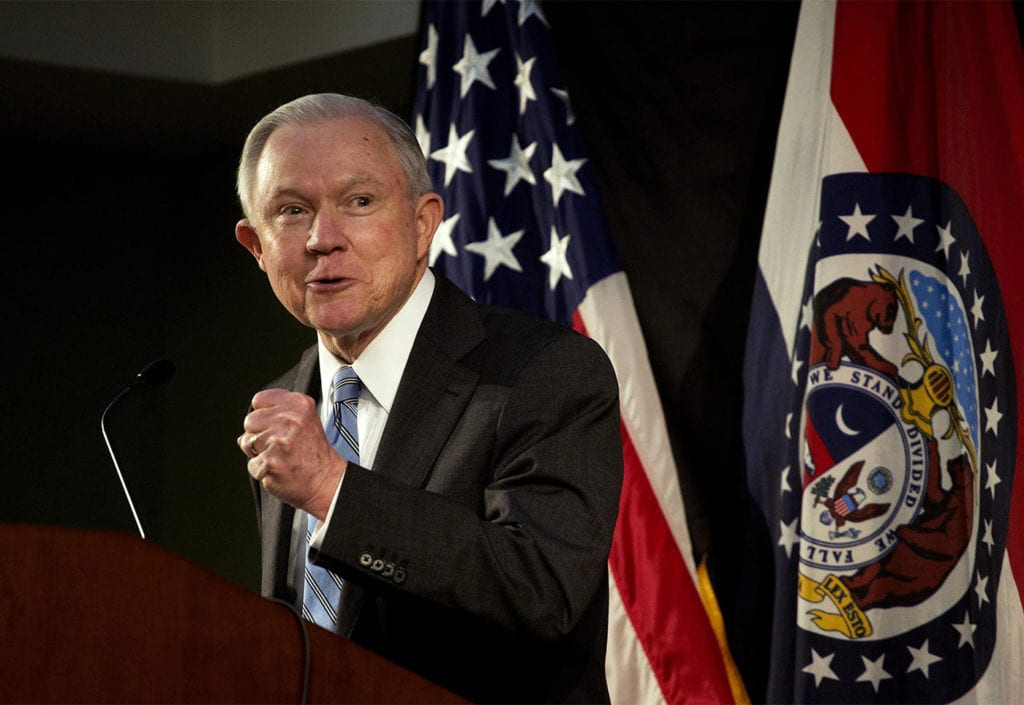

WASHINGTON, DC — Sentencing reform advocates and educators across the state and nation have lambasted a declaration by U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions ordering the nation’s U.S. District Attorneys to seek the harshest of federal penalties for alleged federal offenders including mandatory minimum sentences for low-level illegal drug offenders.

The sweeping declaration was issued earlier this month and comes on the heels of several years of progressive criminal justice reforms achieved on a bi-partisan level in a variety of states, including Tennessee and Alabama.

In the recent announcement regarding the “charging and sentencing policy” for the Department of Justice, Sessions declared. “…it is a core principal that prosecutors should charge and pursue the most serious, readily provable offense… By definition, the most serious offenses are those that carry the most substantial guidelines sentence, including mandatory minimum sentences,” he said.

Within hours of his announcement, there was an avalanche of protests from across the political and social spectrum. The Sentencing Project, the Washington, D.C.-based organization advocating criminal justice reform for several decades was among chorus of groups ranging from The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM) voicing disappointment with the decree.

The move by General Sessions, a law-and-order conservative Republican and former U.S. senator from Alabama, effectively reverses progressive criminal reform programs of the eight-year Obama Administration. It restores a criminal justice agenda criminologists and crime reform advocates say is unwarranted and unfounded based on criminal science studies of the last two decades.

“This (the Sessions decree) takes us back to the 1930’s,” says veteran criminal and constitutional law professor Larry Woods, a civil law attorney who has taught at Nashville’s Tennessee State University for two decades. “It’s tragic, it’s tragic,” says Woods, asserting implementation of the new policy toward low level offenders “just makes it harder on the oppressed.”

The reversal in the federal approach to prosecuting alleged offenders will have a “devastating” impact on the growing bi-partisan criminal justice reform movement in Tennessee and other states, said Dr. Sekou Franklin, associate professor of political science at Middle Tennessee State University.

Sessions’ order offers “political cover” to President Trump and extremely conservative politicians who have ignored and questioned the findings of criminal justice studies, said Franklin. It “serves as a sign post to stop those reforms,” said Franklin, offering an overview of the Attorney General’s brief announcement.

With an estimated 100 federal district judge posts likely to be open for filling during Trump’s first term in office, Franklin voiced the opinion of others interviewed who said Sessions’ declaration could also b seen as a “signal” of there being a litmus-test of sorts used in narrowing prospects for a judgeship. A prospect’s view on use of harsh federal penalties, like mandatory minimums over no prison punishments for first-time non-violent offenders, could come into play, he said.

Sessions’ announcement did follow President Trump’s style of major bark and less initial bite, some observers said. They noted some of his language left latitude for district attorneys to exercise their discretion.

“There will be circumstances in which good judgment would lead a prosecutor to conclude that a strict application of the above charging policy is not warranted,” Sessions wrote. “In that case, prosecutors should carefully consider whether an exception may be justified,” Sessions wrote.

Exception language noted, criminologists and sentencing reform advocates insisted the overwhelming tone and context of Sessions’ statement made it clear he has no interest in the growing efforts in support of punishment that stresses alternatives to long prison sentences.

Returning to law-and-order, lock-them up rhetoric and policies for low level and first time offenders of non-violent crimes—many of them college bound and college students– runs in the face of growing bipartisan efforts across the nation to use incarceration as a last resort, especially in cases involving first-time, non-violent offenders.

“This policy just lacks imagination,” says criminologist Charles Adams, coordinator of the Criminal Justice Program at Maryland’s Bowie State University.“The administration is determined to roll back all the progress of the last eight years,” Adams says.

Adams was echoing peers across the nation responding to a brief statement last Friday by former Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions, now the nation’s new Attorney General. The statement effectively reversed nearly a decade of efforts by the Obama administration to defuse the get-tough stance of the federal government regarding illegal drug traffic dating to the Reagan Administration and beyond.

“We’re back to where we were when (Ronald) Reagan took office,” says Dr. Dorothy Dillard, veteran sociologist and chairman of the department of sociology and criminal justice at Delaware State University.

“It defies everything research shows,” says Dillard, ticking off studies over the last few decades that show harsh punishments of offenders don’t work.

“It’s a more social and health issue than a safety and violence issue,” Dillard says, citing Sessions history of not embracing the studies and findings of sociologists and criminologists.

“There’s absolutely no evidence it ever worked and will work,” said Dr. Vickie Jensen, acting chair of criminology and justice studies at California State University Northridge. Jensen, who has focused on criminal justice studies for 20 years. Jensen, considered an expert on women in prison issues in California, says criminologists across the political spectrum are in agreement harsh penalties on low level offenders have no effect.

“This (Trump) administration has a very different relationship with research scientists”’ says Jensen, citing research by the American Society of Criminology that shows harsh sentences have little, if any, impact on low-level crimes.

For sure, the Sessions decree reflects a frightening turn of events for those fighting for more practical sentencing laws and prison diversion programs, says Kemba Smith Pradia. She is the former Hampton University student whose mandatory minimum federal prison sentence of 24 ½ years drew national attention to lawmaker’s trend toward embracing harsh sentences as a weapon against crime.

Pradia’s parents visited Nashville colleges and churches several time during her incarceration seeking support of their efforts to free their daughter from federal prison.

Smith Pradia was a low level, first-time, non-violent offender, when she was among a group of 21 people indicted, many of them first-time, non-violent students like her.

“It’s just going back in time,” says Pradia, whose sentence was commuted to time served—six an a half years–by then President Bill Clinton in December, 2000. She since has returned to college, earned a degree and joined campaigns for sentencing reforms.

Pradia was at the White House in April, 2016, giving then President Obama a hug for his embrace of efforts to reduce and or commute the prison sentences of thousands of people swept up the the 1980’s and 1990’s wars on drugs.

Obama had also quietly gotten funds for the Justice Department’s Smart on Crime programs to fund local anti crime efforts and got some Pell Grant funds used for `pilot’ programs funding college education efforts aimed at felons readying for transition back to civilian life.

Before Obama left office he had commuted the sentences of more than 1,000 felons, including half a dozen from cities around the State of Tennessee. Thousands of low level offenders serving unusually long federal prison terms was left for the next President.

Many say they felt Obama was giving the next President a challenge to build on the momentum of the criminal justice community and on Capitol Hill to do more. This month’s actions, says Pradia, suggests the outlook for the next several years will be to do less to help those swept into the so-called war on drugs and reverse gears.

“He seems totally disconnected,” Pradia says of President Trump. “I knew it was a long shot,” she says of the prospects Trump and Sessions would build on the gains of the last decade. “I hope Congress gets itself together,” she says.

Federal elected officials from Tennessee have been noticeably silent on Sessions’ declaration, a troubling fact for criminal justice reform advocates.

“We’re going to resist,” Sessions’ order, said Nashville attorney and activist Walter Searcy, chairman of the justice committee of Nashville Organized for Action (NOA). “In the courts, in the streets,” Sessions’ decision will be challenged, Searcy said.